Step Lab Synthesis: Technopedagogical Support for Writing

Last Spring, VTE held a lab on tools to support student writing. This November, we revisit these issues while learners are challenged into producing diverse texts.

November is for Writing

Back in the Spring, Vitrine technologie-éducation (VTE) gathered diverse practitioners and experts to explore technology related to writing. Released months after the end of this period of exploration, this synthesis serves as a follow-up to those activities. Thankfully, a few events occurring this month underline the timeliness of this report. Not only is November the context for both National Novel Writing Month (#NaNoWriMo) and Digital Writing Month (#DigiWriMo), but software publisher Druide just announced an English version of Antidote, its flagship grammar checking solution.

Image courtesy of National Novel Writing Month.

The list of corporate sponsors for NaNoWriMo reads like a catalogue for writing support tools. Since 1999, that event has been motivating large numbers of people to write long form text. Through a month-long writing challenge,

word counts serve as a basis to track progress. Important connections can be drawn with much of the work we do in tracking students’ work.

Writing Matters

In almost any academic discipline, writing is a central component of learning processes. Even work based on musical or mathematical notation may be conceived as writing, to a significant extent.

At the risk of coining a term, one might say that postsecondary education is “scriptocentric” in that it focuses on writing. As some pedagogues argue, however, literacy may shift in relevance according to context. In fact, some technologists are quick to point out the creative potential of non-literate learning, such as 3D printing and other methods of digital making. Away from the core discourse in education, these practices serve to emphasise the scriptocentrism prevalent in contemporary pedagogy.

Writing’s centrality in Higher Education gave us ideas for a lab on technology to support student writing. The lab’s purpose was to bring together diverse practitioners and experts who share concerns about learners’ writing proficiency. From teachers to software developers, lab participants were able to share insight on several issues related to working with student-created texts.

Three separate online lab sessions were organised to address major themes linked to student writing. During the first lab session (held on February 19, 2015), participants grappled with tools and issues related to feedback, assessment, and grading. On March 11, a discussion of assistive technology and the adaptive usage of existing tools helped us put challenges to writing, such as “learning disabilities”, in their proper context. Though focusing on training tools, the lab’s final session (April 7) covered a wide range of topics, from the privacy implications of online writing to teachers’ reluctant adoption of some tools.

In parallel with these online sessions, several elements related to the lab have come on VTE’s radar and the present synthesis integrates issues which may have only been mentioned in passing during lab-related interactions. In other words, the live interactions through videoconferencing software were the most visible part of a broader action on the relationships between technology and writing in college-level education. Topics mentioned during the lab often opened up deeper work.

Through the lab, notes have been collected through a collaborative document. Norm Spatz, a celebrated figure in the Cegep network, has graciously provided summaries for all three live sessions (step 1, step 2, and step 3). Links have been compiled to serve during the lab. Based on the lab’s discussions, an article the pedagogical impact of online distribution of text has been published. Furthermore, our work on the pedagogy of writing unearthed further issues in the appropriation of innovative technology in diverse learning contexts. For instance, tools and platforms enabling active online reading have emerged as a key issue for the future of online learning and teaching.

Writing Policies

From the start, a key issue has provided part of the context for lab: language-related policies throughout Quebec’s Cegep system.

Unsurprisingly, most colleges require language skills to be assessed in any written assignment, regardless of the discipline. College programs across the province have developed specific policies on the “language of instruction” (English or French, depending on the institution). It seems that the most common assessment practice concerning language through the Cegep network (especially among Francophones) is to set a certain percentage of a written assignment’s final mark (say, 10%) which can be used to cover language-related mistakes, such as typographic errors. However, there is a degree of variability in terms of specific policies adopted by particular colleges. For instance, Cégep de Sherbrooke allows language quality to carry as much as 30% of a grade for work done in a course.

Such policies are typically part of a college’s “Institutional Policy on the Evaluation of Student Achievement” (IPESA; PIÉA in French). For instance, Champlain College’s IPESA includes Standards of Literacy and Proficiency in English which dictate that “a maximum of 20 % can be set aside for aspects of English proficiency” in courses primarily addressing competencies other than those related to the English language.

O’Sullivan College, for its part, includes a “Literacy Policy” in its own IPESA. According to this policy:

For all written assignments, spelling, grammar, and structure will be evaluated and will count for 15% of the mark. This evaluation will appear as a separate mark on each written assignment.

Heritage College creates a distinction between formal essays and other written evaluation activities. In a reference document (available as a PDF), Heritage requires language assessment to carry 20 to 30% of the total mark for an essay and 5 to 20% of the final mark for other written assignments.

Language Everywhere

Such policies challenge the notion that assessing the quality of written language would be the exclusive prerogative of language teachers. If a teacher requires students to write a lab report in her chemistry course at O’Sullivan College, that institution’s IPESA requires her to evaluate “spelling, grammar, and structure”.

Such a commitment to “literacy across the curriculum” (as O’Sullivan calls it) underlines the importance of “Writing Across the Curriculum” (WAC). As a cross-disciplinary educational reform movement, WAC encourages diverse types of interactions in Higher Education, from libraries and academic disciplines to student affairs and English as a Second Language (ESL) programs. In this context as in many others, collaborative practices among diverse players may hold the key to meaningful change in learning and teaching.

Writing to an Audience

Language teachers, especially those involved in ESL, have provided key insight on language matters. Among those issues is the simple yet profound impact of writing for a specific audience. Teachers in non-language fields may hold a rather limited perspective on the quality of a text. Some may think of a badly written assignment, full of typographical and grammatical mistakes, as the problem which needs to be solved. They may also hold the standards of academic writing as an unrealistic goal. But the quality of a piece of writing can be assessed in a much more multidimensional way, paying attention to context and purpose. Despite the fact that they may be irritating, few errors in punctuation may have very negative an effect on a geography report. On the other hand, structural issues can prevent the same report from demonstrating key competencies. By putting texts in context, instructors can understand the importance of writing through the learning process.

As some WAC scholars put it, learning can be conceived as “accessing disciplinary discourse”. In a similar vein, the famous Canadian pedagogue Stephen Downes recently described the importance of field-specific discourse in physics (starting around 0:27:42 in the audio recording, emphasis added):

To be a physicist isn’t to know a bunch of facts about physics it’s to act like a physicist, think like a physicist, talk like a physicist.

Clearly, field-related language is a decisive part of the competencies acquired by Cegep students. Often the context for jokes about the need for erudition at “cocktail parties”, the ability to “talk like an expert” can have a profound impact on a college graduate’s career.

Sociologists have long pointed out the importance of social class in academic success. We may attribute much of this effect to language mastery. As they grade a large number of assignments couched in less felicitous language, teachers may become quite impressed by the work of eloquent, highly literate learners. In such a context, it is possible for those teachers to assign high marks to a paper despite flaws in the work accomplished.

Similar effects may carry through work done outside of academic institutions. As is well-known, workplaces can be unforgiving. Something as simple as ineffective word usage in a presentation slide could be cause for dismissal, in some work environments. Teachers can help future professionals avoid a lot of grief by cueing them to the importance of appropriate writing.

Online, another side of communicative competency shows up: the importance of informal writing. The bane of many teachers, “text speak” serves an important purpose in fast-paced written interactions. Failure to use some common abbreviations not only decreases the pace of such an exchange but it may contribute to social stigma. If avoiding “academese” is useful advice for graduate students, it becomes a necessity in much online communication. Few Cegep teachers are equipped to help learners in their use of text speak. But distinguishing schoolwork from chat can help teachers grok the contextual dimension of writing.

Empowering Feedback

As described by a lab participant, teachers can play the role of allies in the “war” against those mistakes which are caught by others, including software checkers. While part of a teacher’s role is to evaluate students’ writing (even outside of language-related disciplines), texts are likely to be judged even more harshly by other people, from potential employers and colleagues to résumé-screening software. By helping learners in their process of appropriating language, teachers may act more like guides than like judges.

A significant portion of the first lab session was devoted to what amounts to appropriate feedback on learners’ writing. Grading may be an unrewarding task, for many teachers, especially when students obsess over their grades instead of focusing on the learning process. But working with learners as they develop their core competencies can be gratifying for everyone involved.

Rubrics are among the chief weapons in a language teacher’s arsenal. While they may appear less sophisticated than most computer-based technology used in teaching, they represent a key development in grading methods. Not only may rubrics save time in the marking process, but they help teachers position themselves as guides instead of judges. In the same vein, scaffolded feedback or the identification of a few key issues in a learner’s writing can prove more effective than a page full of red ink.

As suggested by lab participant Nicholas Walker, the “voice of the reader” can prove more effective than the “voice of authority” when providing feedback on learners’ work. Pushing the notion of “voice” even further, lab participants have mentioned audible and even video feedback on several occasions. In this respect, “screencast” applications are quite remarkable as feedback tools.

Insight from language teachers about feedback on learners’ work has caused some epiphanies among lab participants. Once teachers in diverse fields start thinking of their work as specialized language training, some important innovations can occur.

What’s Tech Gotta Do With It?

Some important aspects of the lab could help any teacher, regardless of the role given to technology in learning. Yet the lab was about tools which can help teachers and learners deal with diverse aspects of learning.

VTE typically adopts a technopedagogical approach in the sense that pedagogy should be primary, with tools playing a supporting role. This lab was no exception to this emphasis on learning experiences, but several tools have been mentioned through live sessions as well as other interactions.

Several guests and participants in the lab have direct connections with specific tools since they either develop, promote, or provide support for them. Such is the case for:

– Nick Walker (Corrective Feedback and Virtual Writing Tutor)

– Gabe Flacks (NewsActivist)

– Avery Rueb (Ready to Negotiate)

– Stefan Sinclair (Voyant Tools, BonPatron, SpellCheckPlus)

– James Bennett (Urkund)

– Grace DuVal and Kim Larsh (Dragon NaturallySpeaking)

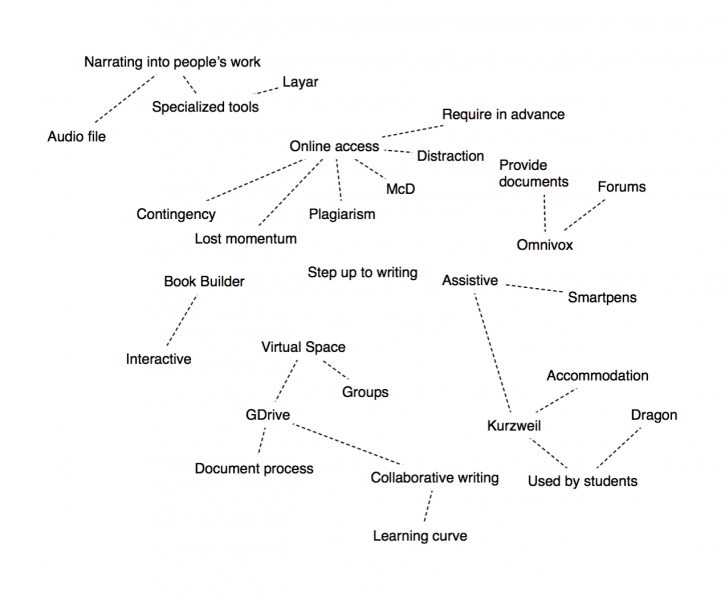

A face-to-face activity with teachers at Centennial College allowed us to brainstorm about technology which can be used to deal with a variety of challenges. Because Centennial teachers follow principles from Universal Design for Learning, most of the solutions discussed can be used by anyone, whether or not they perceive to have special challenges. However, creative uses of such technology represent a specific type of innovation. For instance, according to a teacher at Centennial, the “vision layers” feature of Augmented Reality application Layar could be used to provide feedback on a learner’s assignment accessible through a device, as though the commentary were floating on top of the original text.

Check Your Language

A variety of spelling and grammar checkers have appeared relevant to lab participants (including some who had created such software). While these writing tools are so commonplace as to be invisible, they still deserve special attention in pedagogical contexts.

In teachers’ circles, students’ use of spellcheckers is known to be an issue, especially in language courses.

As an analogue to the use of a calculator in a science class, spellcheckers can bypass a significant portion of the learning experience. Once it has become so easy to check a word’s spelling (or find the result of an equation), the thought process behind proper spelling shifts significantly. Many of us have grown quite used to the process of automated spellchecking, to the extent that we often forget the skills required in deeper proofreading. In this sense, a spellchecker can be a type of “crutch” if used improperly. As with any tool, though, there are more appropriate ways to use spellcheckers (and grammar checkers) in learning contexts.

One method to make language checkers relevant is to focus on certain types of mistakes. Such a strategy has been used by teachers in the lab who had worked on such checkers. In creating grammar and spellcheckers, both Stefan Sinclair and Nick Walker have focused on identifying errors frequently made by second-language learners instead of correcting those mistakes. The nuance may sound subtle, but the effects can be radically different. Instead of telling language learners that a text having gone through a checker is “correct”, software developed by those teachers helps learners perceive how their writing can improve.

General purpose grammar and spellcheckers can have a similar impact on language training, especially if they are used with some guidance. Ginger, for instance, is a subscription-based language checker which offers some language coaching features.

While the lab’s activities were conducted in English and most language teachers involved in the lab focus on Quebec’s main minority language, Druide’s French-focused Antidote has received a significant degree of attention through the lab. Through both live lab sessions and other interactions, several English-speakers have expressed their desire to find an equivalent to Antidote in their native language, something which only happened after the end of the lab’s activities. Part of the reason for English-speakers’ interest in Antidote may be that the application’s approach to spelling and grammar focuses on providing adequate suggestions in a form of “computer-assisted proofreading”. While Antidote does flag potential errors as a word processor’s spellchecker might, its strength lies in the explanations given for some of the corrections. In some cases, comments on some potential mistakes almost take on a conversational tone, as though the software were asking the author: “is this what you meant?”. As we know, tone matters a lot in writing. An English module for Antidote now exists. It identified some mistakes in this synthesis. However, the depth of explanation provided the checker varies according to language, with comparatively shallow analysis of English mistakes. Further, some awkward suggestions reveal that Antidote’s parsing of the English language affords improvement.

Several other tools can be used by learners to get feedback on their writing. Empowering learners represents a strong thread through higher education where many of our students are responsible adults. The hope is that appropriating writing support technology can enhance the reflexivity needed in authorship.

Automated Feedback

Part of the technological context for this lab is an ongoing trend towards automatic assessment. Educators and inventors have long dreamt of providing automatic feedback on student work:

The earliest known patent awarded by the US Patent Office was to H. Chard in 1809 for a “Mode of Teaching to Read.”

These days, this domain of activity concerns projects at technology companies, including a Gates-funded startup which antiplagiarism firm Turnitin acquired, a year ago.

In some cases, media coverage of these projects may put them in direct competition with teachers’ roles. However, as LightSide founder Elijah Mayfield has it, tools such as LightSide’s (and now Turnitin’s) own Revision Assistant are meant to empower learners instead of replacing teachers.

Granted, the shift to self-directed learning and training may have an impact on the roles played by instructors. Such a push is technopedagogical in the sense that it comes from a long-standing tradition in pedagogy (from Vygotsky and Piaget to Illich and Papert, all the way back to Rousseau, with necessary caveats) yet it finds support in technological trends.

Adaptive training material may provide a key example of technology supporting a self-directed activity. Lab participant Kevin Lenton’s clever approach to responsive quizzes uses a branching feature in Google Forms to create self-graded quizzes in a way reminiscent of early prototypes for “teaching machines”.

Teacher as Software Developer

An unexpected component of our lab on writing support tools is the connection between three guests who primarily work as teachers in the Cegep system yet also take on roles in software development project. From Vanier, for instance, French teacher Avery Rueb is a co-founder of Affordance Studio which designed language learning games among other things. Gabriel Flacks, Humanities Department Coordinator at Champlain College in Saint-Lambert also founded NewsActivist, a platform for collaborative learning and teaching. Nick Walker, for his part, teaches ESL at Ahuntsic while publishing books and software meant for language learning, including a unique tool to assess field relatedness. In addition to these three Cegep teachers, McGill professor Stefan Sinclair has also led or contributed to software projects such as Voyant Tools for textual analysis and BonPatron grammar-checker. Finally, other guests involved in technology companies have a background in teaching, including James Bennett who currently works for antiplagiarism software Urkund and used to teach English.

Granted these software-savvy teachers may not be representative of a major trend in higher education. However, their participation in the lab helped make an important point about technopedagogy: it covers all fields, including languages and humanities. These teachers’ experiences with software development helped us gain valuable insight about technological appropriation which extends beyond a specific area of expertise.

Tool adoption represents such a major portion of technological appropriation that some may confuse the two processes, especially in relation to integrating technology for classroom use. Many vendors, who conceive of the educational sector as a wide market, may advertise directly to teachers, including during conferences and other events. Yet the pattern by which teachers select devices or software for pedagogical purposes can be as complicated as any procurement. Whether or not costs are involved (such as in software licences or hardware purchases), the teacher’s institution is likely to be part of the decision-making process. Convincing teachers that a certain device or piece of software can solve perceived problems in education is an important part of the negotiation, but many other dimensions can prevent adoption. Adequate training takes special meaning when a technological solution has to be used by teachers. Remarkably, learners are rarely involved in this type of tool adoption.

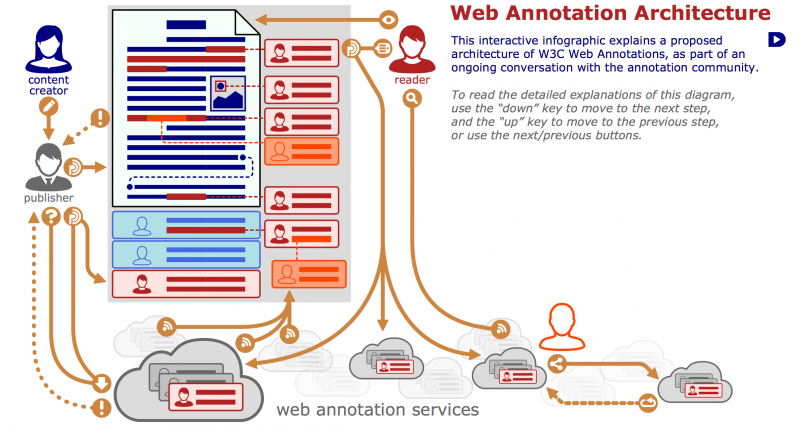

The Emergence of Digital Annotations

Digital texts afford sophisticated annotations. At the end of the lab’s activities, several paths led to the emerging technologies behind Web and eBook annotations. From work on standards to the pedagogical potential for annotations, extending online texts through the process of active reading opens exciting possibilities.

Among stimulating developments, please note a project by a college teacher who collaborated with her class in:

- creating an Open Anthology of Earlier American Literature on the Pressbooks web-based book publishing platform;

- annotating it through the Hypothesis annotation system.

For instance, this chapter was annotated a month ago.

Who knows, maybe the lab’s work will become the basis of new texts annotating texts which annotate other texts?

Texts, all the way down.