Free software, Freeware, Open, Proprietary, and Cloud-based: How to Make Sense of it All?

A great deal of confusion continues to exist around the terms open-source software, free software, and other software that is known as ‘proprietary.’ There are already a number of terms out there without adding the notion of cloud-based software to the mix. Let’s try and make things a little clearer.

In a prior article I wrote about integrating the use of Creative Commons, which states the conditions of use for content created by a third person. However, the use of software is dependant on an end-user licence. This licence stipulates the conditions of use that are granted by the author (or publisher) of the software.

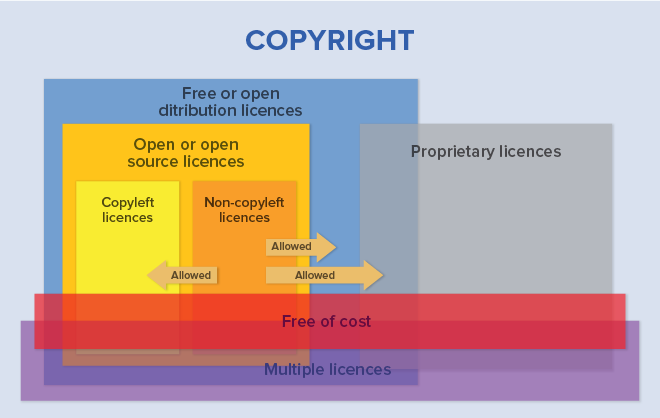

The cost, as sensitive as we all may be to this element, is not the key factor that allows us to properly classify software into different categories.

Licence classification for intellectual works (source: Wikipedia).

Have you ever noticed that we use only one word in English to express ‘liberty’ or ‘no cost’ (the word ‘free’)? For this reason it is easy to associate free software with freeware. They are not the same thing. Even though free software does not cost anything, its key feature lies within the 4 principles of freedom as outlined by the Free Software Foundation (FSF) in order to permit users to maintain their autonomy in the face of proprietary software publishers. This international movement, which sometimes has important philosophical cleavages, recently celebrated its 30th anniversary. It has many members, as evidenced by the impressive inventory of close to 6500 free and open source software contributions.

According to the 4 freedom principles of the FSF, a computer program is free and open source if you, as a user of the program, have the 4 following essential freedoms:

- The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose (freedom 0).

- The freedom to study how the program works, and change it so it does your computing as you wish (freedom 1). Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

- The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor (freedom 2).

- The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others (freedom 3). By doing this you can give the whole community a chance to benefit from your changes. Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

Source: What is Free Software? The Free Software Foundation

In 1998, a rift within the movement led to the adoption of a new strategy towards the concept of free software (Open Source). Open Source Initiative (OSI) protects the right to use, distribute and make source code available as well as the ability to modify it. The emphasis is placed on the availability of the source code rather than the freedoms of the user.

In Quebec, a collective college database of free and open source as well as freeware was developed by the IT-Representatives Network (Réseau des répondantes et des répondants TIC – REPTIC) and the ADTE (Association pour le développement technologique en éducation).

It should be noted that even if open source software is free, the services offered to accompany their implementation are not, whether it is related to purchasing the computer that will host the software, or covering the salary of the person that ensures that it is functioning correctly. For this reason, it is not unheard of to subscribe to training or support sessions that accompany the implementation of software which has been downloaded for free from the Internet. For example, a number of colleges in Quebec subscribe to the services provided by Moodle-DECclic, a learning management system for the colleges that is based on Moodle – a free and open source software platform.

On the other hand, software that you can install for free is not necessarily free in the sense of freedom. For example, Skype is offered for free by Microsoft according to a licence that allows you to use the software ‘as is’ without the ability to look at how it works or modify how it works. In the same vein, the Google Apps for Education suite, even though it is offered for free to educational institutions that Google recognizes, remains proprietary software as well.

Finally, you should also note that ‘free’ can be a relative concept, as is the case with the Microsoft Office 365 educational licence, which is offered at no cost to end users if the educational institution subscribes to a recurrent annual contract with the publisher. Should we do without it for this reason? The debate is still topical. It was also the topic of a VTÉ lab.

And What About Cloud Computing?

One after another, the largest software publishers are launching on-line, service-based subscription versions of software that we traditionally had the ability to install on our computers and use for several years. In other words, the publishers are now weaning users away from their right to use a piece of software to a monthly payment per user, in most cases. Cloud computing is a new way to consume software, which offers its share of possibilities, but… This change is not without its consequences, as much from a financial perspective as from a techno-pedagogical and computing perspective.

Personally, I think that above and beyond the open/proprietary debate, whether cloud-based or not, the real issue relates to the availability of features to download data in cloud-based computing and the use of open formats and data that allow the “freedom of choice” for the solution that best responds to my needs at the moment. How about you? What is your opinion?