Open Educational Resources (OERs) — An Interview with Pascale Blanc from La Vitrine technologie-éducation

Would you like to share an educational resource that you have created with an open licence? Would you be ready to allow others to modify the resource or not? How about letting people use the resource for commercial gains? To help you decide, I recently interviewed Pascale Blanc, the Coordinator at VTÉ (Vitrine technologie-éducation) who also serves as a board member for the ADTE (Association pour le développement technologique en éducation).

Pascale Blanc, Coordinator of VTÉ

What is an OER?

According to the UNESCO’s 2012 definition, “Open Educational Resources (OERs)” include teaching and learning objects and research which exist in the public domain or which have been published with an open licence. The OERs can be in a digital or other format.

According to UNESCO, an open licence confers free permission in perpetuity to:

- Access the resource

- Use the resource

- Adapt the resource

- Redistribute the resource

These free permissions do not hinder the author from asking for recognition for their work. The open licences respect the authorship of the work (those using the work must cite the creator of the resource that is being used or adapted.).

Can an OER be modified?

In line with the definition above, for an OER to truly be an OER, modification of the work must be permitted.

Sometimes, people refer to a resource as an OER, when the reality is that it is not truly open: You can use it for free, but cannot adapt the work. This means that when we think about its “openness” or having access to the resource at no cost that we aren’t thinking about having the control or the “freedom” to do what we want with the resource.

In my way of thinking, for something to truly to be an OER, it is necessary to include the right to modify the resource. This way, it can:

- Be adapted to different educational contexts

- Be translated

- Be adapted for learners with certain disabilities

- Be updated to avoid becoming obsolete

Richard Stallman, the guru of free, libre and open source software, says that it is very useful to be able to modify an OER, since there is a functional dimension that is “like a recipe.” Not everyone has the same need. Quite the opposite. There is no real utility or legitimacy to adapt an editorial presentation, a testimonial or an artistic work. For this reason, their licences can be more restrictive.

Pascale goes even further, inciting me to consider the tools that are used to create or modify OERs.

For a resource to be freely adapted, it also need to be “easily modifiable.” If people need to use a proprietary commercial software that costs money in order to modify a resource, I haven’t really provided the means for the resource to be modified easily.… Therefore it is not really an open resource.

Are OERs free?

This is what we usually assume. However, the UNESCO documentation is not explicit on this point. We know that the right to access the resource is free, but is the resource itself free? There is a difference! Just think of library books that are loaned for free by libraries.

Pascale explains to me that there are different points of view that exist regarding whether or not OERs are free.

When we distribute a teaching and learning resource with a licence that prohibits commercial use, we impede large publishing houses, distributors or training firms to sell or incorporate the work in a commercial training activity, and to use or to modify the resource when the rights would otherwise permit this for other users. We also prevent independent workers and NGOs to draw the benefits for their clients. As an example, it precludes an association from integrating the work into a training event to help keep registration fees low for attendees, and to use these savings to pay for operating expenses.

Therefore, the authorization or prohibition to use a resource for commercial purposes is a double-edged sword.

Pascale informed me that Richard Stallman is campaigning to recommend that teaching and learning resources be distributed under an free, libre and open licence that allows for commercial use, as is the case for free, libre and open source software. It is also this type of free (as in freedom) licence that is recommended by Données Québec, the collaborative initiative behind Québec’s open data project, for sets of data. According to them, a licence which permits commercial use will help to maximize the possibilities for use and broadcasting of open data.

Richard Stallman is also campaigning for “copyleft.” This is an alternative to “copyright” which supports the common good and allows authors to render their resources free to use, while also requiring those who modify the work to make the derivative works freely available.

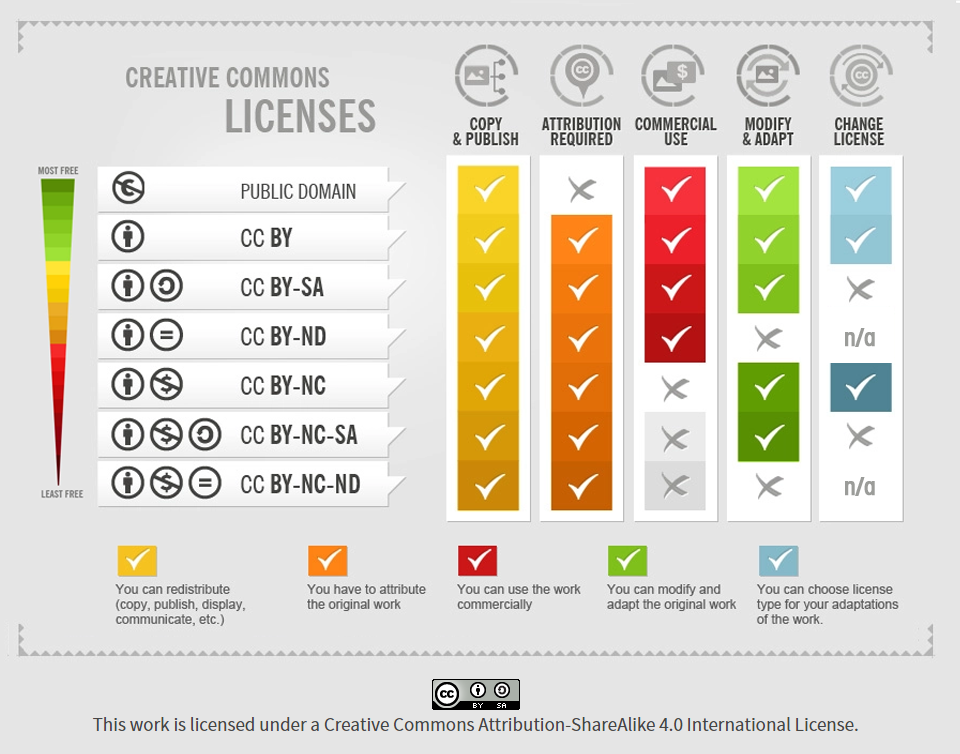

Creative Commons licences

The Creative Commons (CC) licence is a mechanism that allows authors to identify which rights she or he wishes to confer upon users of a work. The copyright reference is always required (the source must always be cited), but the licence specifies:

- If the resource may be modified or not (and it specifies the conditions for rebroadcasting the modified work, if applicable)

- If it may or may not be used for commercial activities

As an example, each of the webpages on Profweb are currently published under a CC BY-NC-ND: Just have a look at the lower right hand side of this page!

As for copyleft, it is in essence a CC BY-SA licence: Attribution and sharing according to the same conditions. This is the licence used by Wikipedia.

The different types of Creative Commons licences (adapted from Foter blog).

To learn more on Creative Commons licences, consult an article on the subject published in 2013 by Christophe Reverd, who was working as a Techno-pedagogical counsellor for the VTÉ at the time.

Pascale wishes that authors who are open to sharing their works develop the habit of attributing open licences to these works the very first time that they are published.

Frequently, when we contact someone in order to obtain the authorization to use and modify an unlicensed resource that they created and published, the person voluntarily accepts. But they haven’t provided an open licence from the get-go… This happened to us when the VTÉ wanted to adapt several videos for the Robot360 project.

It’s good practice to attribute a licence right from the start for a work – to specify which permissions are granted for the work. If you want to reuse a work, it is important to adhere to the recommended practices with regards to how to properly formulate your attribution: Provide the URL for the resource you have modified, for example. Finally, if you have the possibility of also adding a “machine-readable” version of the licence, it’s even better! The resource will be catalogued along with the user’s rights by search engines.

A Google Images search for images that may be freely used and distributed.