Peer Instruction in Arts and Letters

Finding ways to involve students in classroom learning is a challenge, especially for teachers whose own experience of education, like mine, is almost entirely based on the traditional lecture format. As an alternative to straight lecturing, peer instruction offers a promising approach to varying teaching methods and encourages class participation. Student discussions of course material prompted by peer instruction result in improved learning outcomes when compared to passive note-taking, many studies show.

Clickers-wireless transmitters that allow students to respond to questions-are tools that enable peer instruction. Clickers are not a teaching method in and of themselves, rather they are the means to an end: they prompt students to frame their understanding of the course material in their own words so that they can transmit this knowledge to their classmates.With this goal in mind, I decided to participate in the Fall 2009 pilot project using peer instruction with clickers initiated by Pedagogical Resources & Training at Marianopolis College in my Perspectives in Arts and Letters I course.

My motivations for using clickers were fairly diverse. I wanted my students to get excited about reading primary sources in advance of class discussions. I thought the anonymity afforded by clicker voting would make it easier for quieter students to participate and receive feedback. Overall, I hoped that peer instruction would produce more interesting teaching and more effective learning.

More students read the assigned texts. The clickers and questions motivated some students to be more active learners, and the results helped identify topics that needed further explanation.

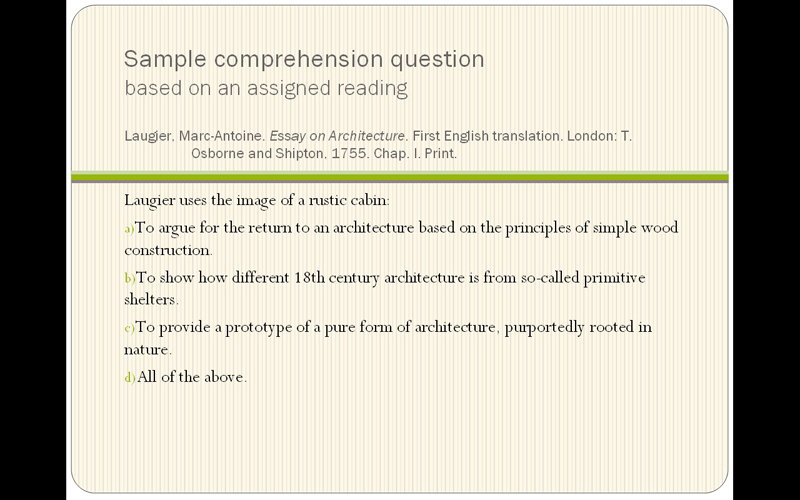

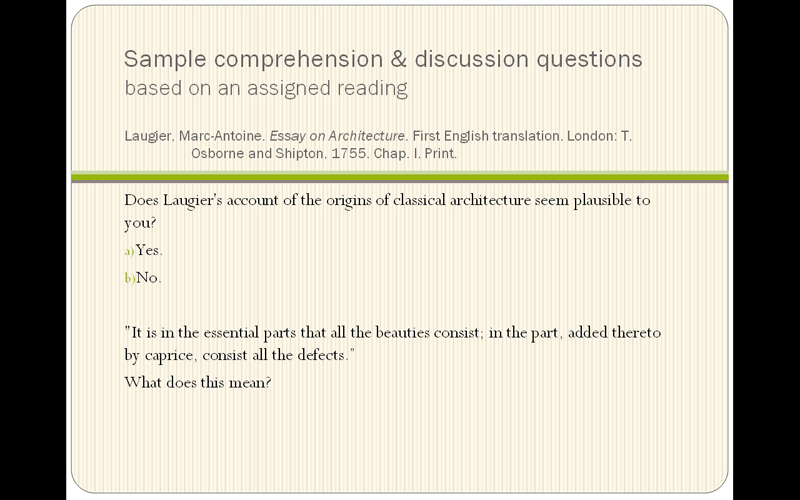

I began small, using clickers only in four classes. On days when I had asked students to prepare a reading, I asked a few multiple choice questions related to the text. The students responded individually using the clickers. I then showed them the breakdown of responses (but not the answer). Whenever the voting was inconclusive, I asked the students to discuss the question among themselves and then to vote again to see if more of them had migrated toward the correct answer. I also used the method to generate discussion based on yes/no opinions and to review material presented in class. A number of slides of questions typical of those I used are below.

PowerPoint Slide containing Typical Questions Used with Students

PowerPoint Slide containing Typical Questions Used with Students

After this reduced-scale trial of the method, I have a number of positive observations. More students read the assigned texts. The clickers and questions motivated some students to be more active learners, and the results helped identify topics that needed further explanation. Using clickers engaged the quiet students in answering questions and the resulting peer instruction added variety to the classroom activities. Several students remarked on the “fun factor” of the clickers, but the novelty will soon wear off.

Obviously, no experience with technology can be totally positive. The factual nature of the yes/no and multiple choice questions that one can respond to using clickers doesn’t easily lend itself to qualitative distinctions and the nuances that are so important in art and literature. Furthermore, students didn’t always read their texts before class. As a result, discussions fell flat when many students were unable to participate fully. The results also didn’t accurately measure their potential to grasp the sense of the texts. On occasion, technical glitches slowed down the class, but adjusting for these will be easier with more experience using the software. It was also challenging to adapt to an arts course a method developed for the sciences: there was not that much information out there on how to effectively use it in humanities disciplines.

The potential of the method to improve student learning-my primary objective as a teacher-certainly merits it.

At the end of the semester, the organizers of the pilot project surveyed the students on their experiences using peer instruction with clickers. Of the 18 students out of 25 who responded, 63% were using clickers for the first time: 89% agreed in varying degrees of certainty that the clickers had increased classroom participation; and 88% felt that they had made the material more interesting. Moreover, 72% felt that using clickers had helped them learn the material more easily; 67% confirmed that the clickers had increased discussion in class; and 61% felt that clickers had allowed them to better evaluate their own learning. The class was split at 50%, however, over whether clickers had helped them to better understand the concepts presented in the course. And although 56% of my students somewhat or mostly agreed that their learning improved because of peer instruction with clickers, a significant part of the class did not.

This last result was not unexpected. The method cannot work unless students participate fully in the process. When they are prepared to discuss the material, peer instruction can provoke wonderful debates; but without preparation there is often little to say, little to debate and little to learn from. Successful peer instruction requires a commitment from all stakeholders.

This observation left me with the question of how to get students to commit to the process if I were to use peer instruction and clickers again with greater success. The next time around, I would present the method and its advantages from the beginning of the semester. I didn’t do this with my test group because I joined the pilot project several weeks after the course began. I would also ask clicker questions more frequently. Students in Perspectives tend to be genuinely curious about the course material, so the benefits of peer instruction, if made very clear and reinforced periodically, should be a strong motivator for them to prepare more thoroughly for class. If this doesn’t work, as a last resort the readings could be linked to an evaluation. While threatening surprise quizzes is not really my style, if introducing them makes peer instruction work better, it will be worthwhile. The potential of the method to improve student learning-my primary objective as a teacher-certainly merits it.

Reading Megan’s article I was struck by the very strong survey results for student perceptions of the effect Megan’s new approach had on their learning. If these perceptions are to be taken at face value, then these results are very encouraging indeed.

I am a firm believer that with a variety of pedagogical strategies at our disposal, every student can be better supported in their learning (and I’d suggest that the development of a range of effective teaching and learning strategies is the hallmark of a skilled teacher). And while no instructional approach promises to reach all students equally (lecturing sure as heck doesn’t!), when 50% or more of the students in a class report that their learning benefited from a new learning method I think we should pay attention. Increased preparation for class, interest in the material, class participation, and meta-cognition are all good indications that learning is happening.

Moreover, feedback to the instructor that more attention needs to be given to encouraging preparation of readings before class is also very useful, and relevant to any instructional approach that I can imagine. If we can get students preparing for class (by carrot or by stick), then the increased engagement aimed at by peer instruction methods might yield some very strong learning gains, or at least help to build the foundation upon which deeper learning is to develop.

Due to the vast number of confounding variables typically present in a ‘live’ educational setting (as opposed to a lab), it is often difficult to determine what effect a teaching or learning intervention really has on student learning outcomes. That’s just the nature of the game. But I was reminded while reading Megan’s article of one of the central tenets of educational research: “do no harm”. Unless a teaching/learning strategy is having a detrimental effect on others in the class, if 50-80% of the students are reporting benefit then we should continue to develop that strategy in order to maximize its effectiveness, even if the other 20-50% are reporting that it does nothing for them. Add hopefully the positive effect on student learning is great enough to justify the investment in instructional innovation that is required to make an approach really work.

So thanks Megan for your willingness to do some of that work, and for sharing with with us all.