Immediate Feedback to Students Using the Branching Feature of Google Forms

As a basic instructional principle, learners need feedback, and to receive maximum benefit from feedback, it should be supplied as soon as possible after an assessment or ideally after each question. I recently experimented with Google Forms to find a way to provide this immediate feedback.

One of the most successful strategies to implement this is the Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique (IF-AT) for multiple choice concept questions. Also known as “scratch card quizzes”, students are given a scratch card (which is like a lottery scratch ticket in that you can scratch off different areas with a coin). There are five options (A to E) for each series of concept multiple choice questions. Students scratch off their answer for each question. A correct answer is indicated by a star after scratching. An incorrect answer, indicated by the lack of a star, gives the student more chances to answer. The student does not move onto the next question before knowing the answer to the previous question. Usually the teacher gives a progressively decreasing score for multiple attempts. Students are highly motivated by this activity, particularly if the activity is framed as a group quiz. A certain buzz is created because students know they have skin in the game, that they will get a reduced grade for each attempt, and each group can work at its own pace. A drawback to this approach is that the teacher has to provide the relatively expensive scratch cards, and there isn’t an automated mechanism for checking and recording student progress. Google Forms can be used to recreate a digital version of this experience that can also be done at home.

Many platforms allow for concept questions to be incorporated into assessments (e.g. Moodle, WebWork, Lon-Capa) and some of these systems can let students know if they have the answers correct at the end of the question sequence, but these platforms lack a feature provided by Google Forms – Branching. That is to say, the ability to change the script of an assignment based on the response to a particular question.

Google Forms are part of the Google Drive tools, and can be accessed from the Google Docs menu. Google Forms are very flexible once they are initiated because they allow for multiple types of data entry (e.g. multiple choice, paragraph text, click boxes etc.). You have the choice of randomizing the order of questions and their potential responses, making questions compulsory, and allowing students to link to their answers. This allows them to have a record of their answers, and to be able to change their answers at a future occasion. The results are stored in an associated Google Sheets spreadsheet accessible only by the teacher, which is updated as soon as the student ‘submits’ their Form answers. This spreadsheet timestamps responses as they are submitted, and separates the student answers to the form questions into different columns. The teacher does need a Google account, but the users do not need an account to participate. The teacher simply shares the hyperlink to the Google Form with the class to make it available to students. However, many institutions are adopting Google Classroom for their classroom management platform, which does give additional flexibility with respect to tracking student login and participation.

I usually start the first page of a quiz in Google Forms with brief instructions and a field for student identification. Because on-line privacy is an issue, particularly with Google, I give my students a non-traceable unique identifier that can be used for all their class-related on-line activities. This identifier is some combination of their last name and student number. Different institutions may have different policies for online privacy.

Example quiz on Google Forms

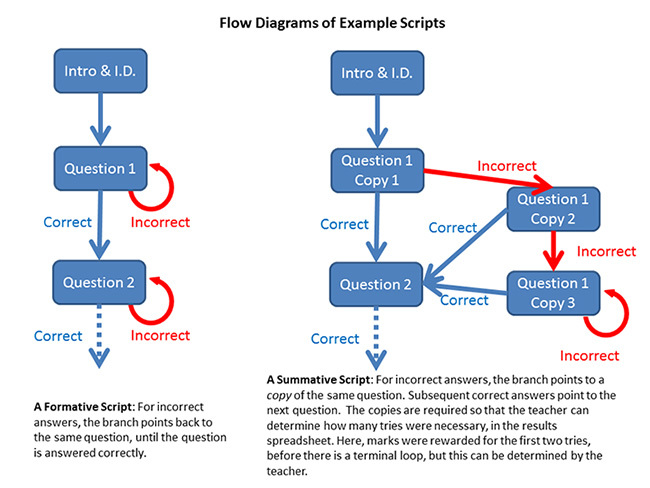

The second page contains the first question. This can be a text-based multiple choice question, and can include images for both the question and the answers. The answer options are easily incorporated into the question page. And it is here that it becomes interesting to use Google Forms since you have the option of sending the Form user to another page for each possible answer, by using a branching technique where the user is forwarded to the subsequent question only when the correct answer is chosen. If not, the user is sent back to the same question for a second attempt. In this way the student cannot move on to the next question until the correct answer is chosen. This script would be perfect for a purely formative assessment, in which only participation mattered. Of course a non-engaged student could simply click through all the answers until the Form allowed moving onto the next question. So for summative assessment a slightly more sophisticated strategy is required.

Visual representation of branching for a formative and summative quiz

To recreate the immediate feedback assessment model, I use a three strikes model. That is to say, in the Google Form I create three copies of the question, one after the other. The first copy is the first attempt. Success on this first attempt is worth full marks and branches to the next question. A wrong answer branches to copy 2 of the question. Success on this second attempt is worth half marks and branches to the next question. A wrong answer branches to copy 3 of the question. Success on this third attempt is worth no marks but branches to the next question. A wrong answer here branches back to this same copy of the question until the student succeeds. Each copy of the student’s attempts will show up in the companion spreadsheet which is linked to the Google Form in a different column for each attempt. It is relatively easy write a logical equation in the spreadsheet to quickly grade the assignment, and to identify students who are trying to trick the system by deliberately answering incorrectly until the third question.

A video tour of the quiz from the perspective of the student and the teacher

Even more sophisticated versions could branch to a completely different question script to handle instances where the student still gets it wrong by the third attempt. This is the basis of Learning Catalytics, and other learning systems that try to personalize and adjust to the student’s learning needs. Ultimately this will be the future of education. But until then, Google Forms provides an easy shortcut to give immediate feedback.

Clever approach!

Some of the earliest designs for “teaching machines” followed the same overall idea, for multiple attempts.

http://hackeducation.com/2015/02/03/the-first-teaching-machines/

During the Google Apps for Education Summit in Montreal, back in December, Chris Webb and others shared a few ways to automate assessment using several tools.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1o0TQp_oBa_BAoqAILfY9WAhXNB3N7BrV2YOqv9unlG8/edit

Sounds like Flubaroo and Doctopus are the best-known tools for this kind of task, but it also sounds like things may be moving fairly quickly.

Something which can help, in formative assessment, is to add comments following each incorrect answer. “This answer is incorrect because…” or even hints like “Think about mass and velocity”. It can be very time-consuming and potentially tricky to add all of these, but the potential to enhance the learning process is significant.

In fact, it could be useful to create those quizzes with students. In my experience, quiz questions created by a group of students tend to encapsulate a salient part of the learning. Funny thing is, those who created the question are quite likely to miss the correct answer, on an exam, probably because of test anxiety.

Thanks for the comment, Alex. I did try out Flubaroo, and unless it has changed, it does not support the sort of branching I describe here. In fact, most tools do not support it. Rather they continue to be very linear. I went to Eric Mazur’s talk on Assessment at McGill, and he talked enthusiastically about the IFAT technique. In fact, now he does not give final exams, but rather a team-based immediate feedback exercise. He described how the anxiety levels in students decreased, and how the exam becomes a learning opportunity.