My 1st experience, at the last minute: novice level

The 1st time I gamified a course (it was the General Chemistry course in Science), I decided to do it just before the start of a new session. I came up with a very simple system:

- For each class a student attends, there is a gain of half a level (for a total of 1 level per week, since we meet twice a week) unless the student arrives late, their phone rings, or they have not done the required preparation work.

- For each “challenge” successfully completed, the student levels up. The challenges are homework assignments.

To compile the data (and determine the level of each student), I used a simple sheet of paper: the sheet on which I usually took attendance. Rather than simply noting attendance, as I’d always done, I noted levels. It didn’t take me any longer.

When students reached certain levels, they earned rewards (mainly linked to the course labs):

Equipment loan

(To access the chemistry labs, students must wear a lab coat. One of the rewards I offer in my game is the loan of a lab coat in case they forget).

Being pardoned for lateness

(Being late to the lab means students cannot access the room. This reward allowed the student to do the activity nonetheless).

Having a right to an extra day to submit a lab report

Having one less section to complete in a lab report

It was a very basic system, but it worked! If you want to give it a try, you can also start with a simple structure like this, then make it more complex the next session if you feel like it!

2nd experience: advanced level

The following session, I taught the course Chemistry of Solutions, in which several students had participated in my first General Chemistry experience. In keeping with the subject of the Chemistry of Solutions course, the theme of the session was magic potions. In addition to levels, I introduced the concept of “hit points”:

- Students start the course with 4 hit points.

- Each time they’re late, their phone rings, or they come unprepared, it costs them 1 hit point.

- When a student runs out of points, they “die.” To resurrect, there are several options:

- bring snacks for the whole class

- write a 250-word text about their heroic death

- prove that they have done all the homework for a class (weekly homework)

- prove that they are up to date in their lab notebook

- Every week, students can earn potions by doing (formative) homework:

- The healing potion allows students to regain hit points.

- The invisibility potion prevents them from leveling down when absent. (“I wasn’t absent, I was invisible!”).

- The energy potion is used to obtain sweets.

- The atmosphere potion allows students to listen to music during exercises.

- etc.

- I’ve also introduced a concept of objects to collect: for example, a personalized periodic table on the theme of alchemy.

I would correct the homework during the break and immediately give it back to the students, allowing me to offer quick and personalized feedback, an important quality of effective homework.

The current version – Classes & Dragons: master level

The most complete version of my game is called Classes & Dragons (students suggested the name).

The characters

Now, in my General Chemistry course, during the 1st class, students are placed in teams of 4. Each student completes a character sheet, writing the name of their avatar, drawing it and choosing a character class: warrior, healer, rogue, or mage.

- The warrior has 5 hit points and the power of protection that enables them to stop a teammate from losing hit points.

- The healer has 4 hit points and the power of resurrection that allows them to save a member of their team from death.

- The rogue has 4 hit points and the power of invisibility: they can avoid the negative consequences of absence (except for summative evaluations).

- The mage has 3 hit points. They have the power of erudition, which grants them an additional 50 experience points from the start.

Each team must contain a single character from each class. At the end of the session, the team with the highest score wins a prize. (I post the teams’ scores on a board in the classroom.)

Experience points, levels, and hit points

Students earn 50 experience points for:

- being present each class

- participating in an extracurricular activity (such as attending scientific conferences at college)

- completing a challenge (like dressing up for Halloween)

- submitting a formative homework

100 experience points allow them to level up.

Students can also lose points for:

- being late

- forgetting their periodic table

- forgetting their calculator

- forgetting their notebook or pencil

- their phone ringing inappropriately

If a student runs out of hit points, they die. The person can no longer earn experience points and must be resurrected by their team’s healer. (This doesn’t happen very often! However, it does give me a chance to intervene with those who have problematic behaviours.)

Data compilation

After each class, I take about 10 minutes to compile the data in a Word document and record each student’s experience points in Moodle’s Level Up! module. I think it’s fun, so I don’t mind those few minutes at all.

In Moodle, students can see their level and experience points. This is particularly motivating for those at the top of the ranking: they want to keep their place and try to progress further.

I’ve also created badges in Moodle so that students can see which powers they’ve acquired (based on the level they’ve reached and their character’s class).

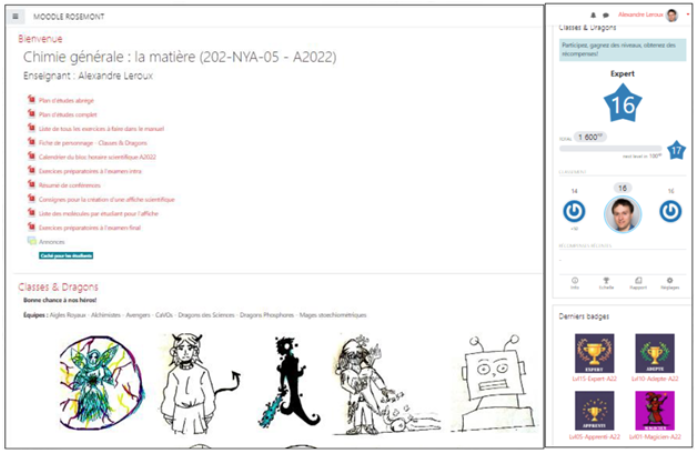

Overview of my course’s Moodle homepage

The rewards

Here are the rewards offered to the students.

| Level |

Title |

Power |

Effect |

| 5 |

Novice |

Invocation |

1 equipment loan (calculator, lab coat, etc.) |

| 10 |

Enthusiast |

Ruse |

+6 hours to submit an assignment (except exams) |

| 15 |

Master |

Extension |

+1 day to submit a lab report |

| 20 |

Master |

Premonition |

1 formative correction of a report section |

| 25 |

Champion |

Influence |

Honourable mention and choice of theme for an exam question |

| Highest level reached by a person in the class |

Hero |

Treasure! |

Gift from the teacher (they were 20-sided dice) |

Artifacts

Each week, I give the students a special homework assignment (which I have time to mark during breaks). Completing the homework allows students to earn a magic artifact (while learning, of course!).

For example, one of the homework assignments asks students to evaluate the colour of Medusa’s eyes by finding its wavelength, based on information provided in the role-play and, of course, on the concepts covered in the course. Students who find the right answer are given a magic mirror. This mirror enables them to redirect a question I ask them in class to the student of their choice. Laughter guaranteed!

Another homework assignment earns the student a crystal ball that lets them see their grades 24 hours before everyone else. The boots of celerity allow them to choose the presentation time for their oral presentation.

Boss battles

I’ve changed my approach to revision classes before exams. They’ve become “boss battles”. I dress up as a monster and the students work in teams (their team of 4 characters). I take turns asking the students questions. If the student succeeds, they wound the monster, while an incorrect answer costs 1 hit point. Whoever defeats the monster gets extra experience points.

Before the final exam, the monster to face is a dragon. A correct answer inflicts 1 damage point on the dragon. But an incorrect answer results in immediate death. The team that inflicts the most damage on the dragon wins.

Dungeons

Obviously, in addition to the dragon, the game requires dungeons. Dungeons are formative exams (my exams from the previous year). I assign a quarter of the questions to warriors, a quarter to healers, and so on. Students have 1 hour to complete their part of the exam individually, then 1 hour to share their answers with members of their class (warriors together, healers together) and record their final answers on whiteboards. I validate the answers, then the students photograph the answers of the other groups to gain access to the answer key for the entire formative exam. The treasure trove (received by all students present in class) was a summary of the session’s material on a double-sided sheet: the students really appreciated this tool.

Student appreciation

In an end-of-session survey, 94% of students said they liked the formula “a little” or “a lot.”

Comparing the students’ final grades with the levels they had reached in the game, I found that, among the students who were most involved in the game (those who had reached the highest levels), were the 3 students with the highest grades in the group as well as the 3 with the lowest grades. I was surprised, but very pleased, since this is a sign that the game engages both stronger and weaker students.

The students in the group that played Classes & Dragons took part in more extracurricular activities than those in a group I taught for most of the term while replacing a colleague and in which I didn’t introduce Classes & Dragons. They also (and this was my main objective at the outset) did more formative homework. I even saw, for the 1st time in my career, students staying in the classroom at the end of the class to do their homework!

Your turn!

If you’d like to design your own gamification system, here are the steps you need to follow.

Step 1: Choose the behaviours to observe

Choose positive behaviours you want to encourage, or negative behaviours you want to discourage, and that are easily observable.