Engaging videoconferencing classes going back and forth between a large group, subgroups and teams

Is it mandatory for a synchronous class session to bring together all students in a group in the same virtual room for the entire duration of the class that would have taken place if it had been taught in a face-to-face setting? No! The use of videoconferencing should not force a linear lecture presentation format.

Recording of the webinar organized by the fabriqueREL [in French]. This conference was part of a series of about fifteen webinars [in French] on distance learning that the Ministry of Higher Education mandated the fabriqueREL to organize as part of the Digital Action Plan for Education and Higher Education.

In this report, I will propose strategies to ” blow up ” large group sessions by replacing them with an assembly of videoconferencing sessions occurring partly in large groups, in sub-groups and in teams, combined with asynchronous content and discussions.

An example to illustrate the essence of what will be discussed: let’s imagine that you give a face-to-face class every Tuesday from 8 to 11 am. Rather than opting for large group videoconferencing sessions lasting 3 hours, you could, for example, split the group into 2 sub-groups that you each meet for 1.5 hours, preceded by asynchronous activities (watching video presentations, readings, etc.). During these sub-group meetings, you could, if you wish, go back and forth between the whole subgroup and small teams conversations. This is just one example, but in this report, I will present different non-linear approaches that encourage student interaction and action.

Table of Contents

- Concepts

- Pedagogical practices

- Technical considerations

- Respective advantages of videoconferencing and asynchronous content distribution

- Flipped teaching in distance learning: optimizing the use of synchronous meeting time

- Different course formats for different “moments” of teaching-learning

- Possible temporal organization of different formats

- Considerations for setting up subgroups and teams

- Tips for preparation and facilitation

- Active pedagogy and the pedagogical relationship are also possible at a distance.

- References

Concepts

This report is based on active learning design as well as on the pedagogical relationship.

The pedagogical relationship

Establishing and maintaining a quality pedagogical relationship [in French] with students has a major impact on their learning, even among adult students in post-secondary education.

The decisive effect of the pedagogical relationship was especially observed for particularly large groups, hence the interest in considering the possibility of in sub-group formats.

Also, a concern for enabling rich interpersonal communication will guide us toward technical choices that allow for rich interpersonal communication, permitting intuitive two-way conversations. As Beaty and Ellis point out, this includes being able to grasp the important nuances that allow:

- seeing fine facial expressions

- seeing body language

- hearing subtle intonations in the voice

Active learning

Research shows that active learning methods generate deeper and more sustainable learning for students [in French]. Moreover, active learning design promotes a gain in student engagement, an often welcome remedy for the diminished attention span in video-based distance learning.

In active learning, faculty no longer relies on lectures as the main pedagogical method. The activities implemented within the framework of active pedagogy can take many forms. The Vignettes de pédagogie active site, hosted by Polytechnique Montréal, lists a large number of them.

Flipped teaching is an approach that has shown to free class meeting time which can then be used for more active learning activities during class meetings.

Flipped teaching

In face-to-face teaching, a proven way to make the most of classroom time (in an active learning perspective) is flipped teaching (flipped classroom). When the flipped teaching approach is implemented in a face-to-face class setting, students are exposed to certain content at home before class (through watching, reading, etc.) so that class time can be used to put students into action.

And active learning at a distance?

If the specifics and limitations of the context and the tools of distance learning are taken into account, there is no reason why the principles proven in face-to-face teaching should no longer work at a distance. However, transposing them requires reflection and creativity. This report proposes strategies to guide you.

Underpinnings of this report

The content of this report is based on the professional and scientific literature I have consulted, but also, more importantly, on the numerous data I have collected by analyzing courses given at the Université de Sherbrooke.

In fact, since 2011, my mission at the Faculty of Education of the Université de Sherbrooke has been to develop ways to support learning and to develop complex behavioural and interpersonal skills through distance learning for students in graduate programs in special education teaching. The transposition of principles and methods that are known to be effective in face-to-face settings to remote learning was central to this endeavor. The experience lasted 8 years and was supported by continuous data collection.

Although the project focused on university education, I am convinced that the findings that can be drawn from it also apply to college education. And although the focus was predominantly on the teaching of interpersonal and human skills, many of the findings are applicable to any discipline. This project serves as a basis for the experience I share here, from a practitioner’s perspective.

Pedagogical practices

Technical considerations

To implement the strategies proposed in this report in a simple manner, you will need access to a videoconferencing platform that allows you to:

- hold a plenary conference with your entire group of students

- divide your students into subgroups, each of which can hold a video meeting.

This is possible in the main video conferencing platforms used in colleges:

- In Teams, you can use the general channel for large group meetings and create other channels for each of the video meetings in sub-groups. This means students can access these rooms autonomously. As of December 2020, breakout rooms are also available. The latter work in a similar fashion as on Zoom, and require the teacher to be online.

- In Zoom, participants can be divided into breakout rooms (either randomly or by manually distributing participants to the different rooms in advance or at a chosen time). (These rooms are accessible only while you are logged in to the Zoom session yourself).

- In Adobe Connect, you can also use breakout roomes. (They are only accessible while you are logged in to the Adobe Connect session yourself).

Some people prefer to use other platforms, such as the open source Jitsi Meet platform, and create several meetings in advance. Students can access these rooms even when you’re not online.

In parallel, to get students to collaborate, it is relevant to provide a collaborative platform for them to work together. For example:

- a Google document on Google Drive

- a shared document on Microsoft 365 (via Teams or otherwise)

- a collaborative whiteboard [in French]

In addition, plan for a way to produce video clips that students can view asynchronously. For example, this can be with:

- OBS Studio

- Microsoft Stream

- Screencast-O-Matic

Respective advantages of videoconferencing and asynchronous content distribution

When considering the design of a distance learning course, keep in mind the respective advantages of synchronous and asynchronous modes.

Advantages of videoconferencing (synchronous)

The ultimate added value of videoconferencing lies in the relationship it establishes between all the members of the group and between you and your students.

- Videoconferencing provides two-way communication between teacher and students, and multi-directional communication between students.

- Videoconferencing allows you to see people’s faces, capture their intonation and non-verbal language.

- Videoconferencing provides rich opportunities for putting students into action in authentic contexts, especially when teaching relational skills or when there are “human” elements in the targeted skill. Videoconferencing allows for role-playing, for example.

To take advantage of the benefits of videoconferencing

In order to benefit (or not) from the advantages of videoconferencing, the size of the group is a key element.

Often, because of the size of student groups, videoconferences “default” to webinars where only the teacher speaks, and students keep their cameras and microphones off. This is not necessarily the best use of a synchronous format. The teacher does not see the students and cannot read their facial expressions to see if they are “lost,” disinterested or passionate.

Advantages of delivering content in an asynchronous format

Asynchronously distributed content can take different forms. These contents can be consulted by students:

- at the moment they are most available

- at the pace that’s right for them

- with as many repetitions as necessary for their understanding

Moreover, when an activity requires a lot of concentration (for example, synthesizing a text), it is often easier for students to do it asynchronously than “live,” at a time when their concentration may not be optimal.

To take advantage of the benefits of asynchronous content delivery

In order for students to take advantage of the potential benefits of asynchronous content delivery, make sure that the content presented is well divided and organized.

For example, if you produce a long 2-hour video presentation, your students may have difficulty finding their way through it and may not bother to watch it more than once to find the segment that answers the question they will ask themselves 5 weeks after their initial viewing of the video.

The problem will be the same if you have several short videos with non-evocative titles (for example: “Bronfenbrenner’s Model, Part 1”, “Bronfenbrenner’s Model, Part 2”, “Bronfenbrenner’s Model, Part 3”, etc.).

If your content is distributed in an unorganized manner (e.g., attached to emails or in forum threads), it will be more difficult for students to refer to it a few weeks after the contents were assigned. It’s a good idea to structure them well to make them easier to find later. They can, for example, be collected in a table of contents within a digital learning environment such as Moodle.

Flipped teaching in distance learning: optimizing the use of synchronous meeting time

The flipped teaching approach can be implemented very successfully in distance learning: students are asked to read or watch content asynchronously before the synchronous sessions. These synchronous sessions can then be used for:

- discussions

- debates

- case studies in teams

- etc.

The time freed up during the synchronous sessions, because the presentation of basic content does not have to be done, can be used to truly interact with the students, thus making full use of videoconferencing.

If you opt for flipped teaching, during the synchronous sessions, put the students into action based on the content that should have been seen asynchronously beforehand. Start doing so at the beginning of the semester.

- Do not fall into the trap of repeating in large groups the content that should have been seen individually asynchronously, even if a few students have not done the work, because students will lose interest in doing the asynchronous activities.

- You might even consider a preparation test (entrance ticket) that students must pass before they can join a team activity. This could be a self-corrected questionnaire, for example, which would be formative, but mandatory.

Different course formats for different “moments” of teaching-learning

To optimize different teaching formats, consider breaking down the traditional concept of the synchronous class session. Don’t hesitate to break out of the belief that a synchronous class should be a 2-hour or 3-hour period during which an entire group of students are gathered together in the same virtual room at the same time.

Analyze the learning sequences for each of your class sessions. Divide your sequences into different teaching “moments” according to the purpose of each portion of teaching. Then choose the most appropriate format for each moment.

Within the same lesson (2-hour or 3-hour time slot), it is possible to combine:

- large group meetings

- meetings in sub-groups

- team meetings

- periods during a synchronous meeting where students are asked to log out to individually watch a video, do a reading, or complete an exercise (in a digital or paper-and-pencil format)

Outside of these time slots, students can do asynchronous activities:

- readings

- watching videos

- written summaries

- assignments and learning exercises

- large group forums

- subgroup forums

- forums with imposed questions

- peer feedback

- reflexive or reflection journal

- etc.

Below is a table that describes different types of teaching moments (not all categories are mutually exclusive) and the preferred format(s) for each.

| Teaching and learning moment | Preferred format(s) |

|---|---|

| Uniformity, predictability All students should receive the same information developed in advance. This is a time for the transmission of content or instructions. E.g.: Lecture |

Asynchronous contents

|

| Uniformity, unpredictability All students should receive the same information that you cannot necessarily predict. E.g.: Time for students to ask questions to clarify assignment instructions. |

Large group synchronous session Possibly to the detriment of the quality of the relationship with each student and the time to be devoted to each student, due to their large numberLarge group forum (asynchronous) Can be time consuming. Slower. Often allows less detailed feedback and fewer feedback loops, but sometimes more accuracy. |

| Interaction and rapport You want to allow students to:

|

Synchronous session in subgroups Simultaneous, sequential or partially simultaneous You circulate on demand or randomly between subgroups. Care must be taken to reserve or repeat any essential clarification of course content or assignment instructions in a large group plenary or in an asynchronous format.Subgroup forum (asynchronous) |

| Implementation You want students to practise. |

Synchronous session in subgroups To be preferred when the learning object has a relational component, for example:

Exercises completed asynchronously |

| Taking the pulse You want to verify what was understood, retained, done or experienced by the students. |

Subgroup session Best optionTeam session To be considered if the group is not too large and you can move efficiently through the teams (meeting simultaneously or sequentially).Large group session Can be a source of inhibition for some students. You will have less time for each student and may not be able to see everyone’s cameras.Asynchronous written exercises Allows you to take the cognitive pulse of what students can do, but it is more difficult to take the emotional pulse of students (unless you choose a reflexive journal or a log). |

For each teaching-learning moment, evaluate the format to be chosen according to the following criteria

- its pedagogical value

- its realism with regard to the time you will have to invest in it

- its compatibility with the planned (or possible) schedule for your course

Possible temporal organization of different formats

Within a planned time slot, meetings and activities can be held at different times. The different formats can:

- take the shape of back-and-forth during the planned time slot

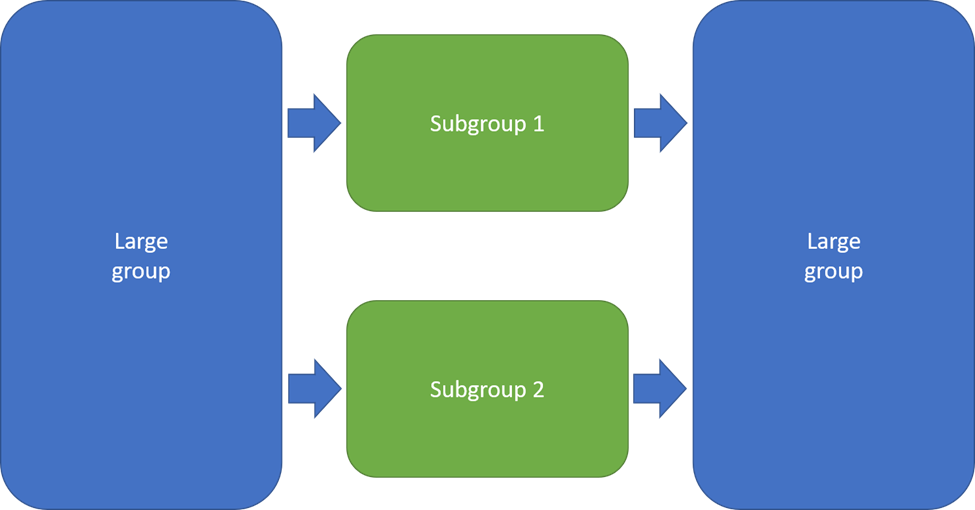

Example of back-and-forth meetings. During a class, you go back and forth between plenary sessions in large groups and meetings in subgroups.

Example of back-and-forth meetings. During a class, you go back and forth between plenary sessions in large groups and meetings in subgroups.

- follow each other sequentially

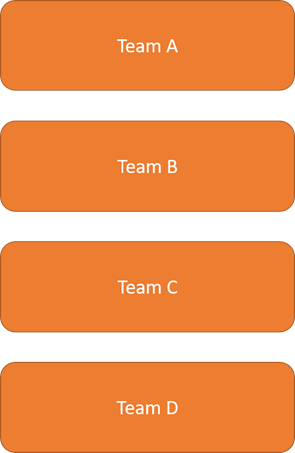

Example of sequential meetings. During a class time slot, you take turns inviting only a third of your group. (The decrease in the time spent by each person in the meeting can be compensated by asynchronous content such as video presentations or readings).

Example of sequential meetings. During a class time slot, you take turns inviting only a third of your group. (The decrease in the time spent by each person in the meeting can be compensated by asynchronous content such as video presentations or readings).

- take place simultaneously

Example of fully simultaneous meetings. Students meet in teams at the same time. You circulate between the teams, on request or randomly.

Example of fully simultaneous meetings. Students meet in teams at the same time. You circulate between the teams, on request or randomly.

- be staggered, but partially simultaneous

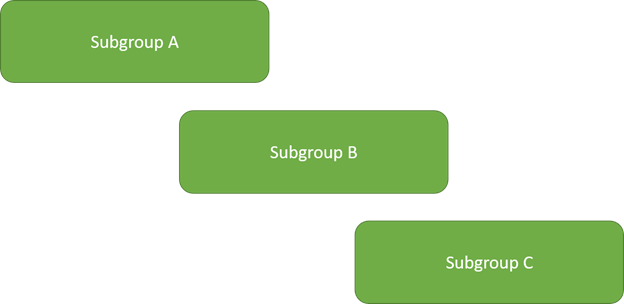

Example of staggered, but partially simultaneous meetings:

Example of staggered, but partially simultaneous meetings:

- Subgroup A meets at 1:00 pm for an activity, then you join them from 1:30 pm to 2:00 pm for a discussion.

- Subgroup B meets at 1:30 pm for the activity, then you join them from 2:00 pm to 2:30 pm.

- Subgroup C meets at 2:00 pm for the activity, then you join them from 2:30 pm to 3:00 pm.

Thinking about time organization could lead to hybrids, for example two sequential meetings of subgroups, each of which goes back and forth between the plenary with the entire subgroup and some time in smaller teams.

It is also possible to insert in your live session planning activities that are not videoconferences, such as watching a video, reading a text or doing a small written exercise individually before returning to the videoconference.

Considerations for setting up subgroups and teams

Logic for setting up subgroups and teams

Sub-groups or teams can be set up in a variety of ways:

- random

This can be done with one click on Teams, Zoom or Adobe Connect. - determined by the teacher (based on complementarity, similarity, etc.)

- chosen by the students

To allow students to choose their teammates, you can, among other things:- Proceed orally in the plenary session.

You could, for example, share your screen while highlighting the names of the students who want to meet in different teams with different colors. - Invite students to write their names in teams in a shared document (on Google Drive or Microsoft 365) or a Doodle (create empty teams in advance).

- Proceed orally in the plenary session.

- thematic workshops through which the students circulate

For example, you create 4 videoconference rooms to deal with 4 facets of a problem (one room to discuss the social aspects of a problem, one room to discuss its economic aspects, etc.).

Stability or change

When choosing the method of setting up subgroups or teams, think about your needs for stability or change for the subgroups and teams.

You can choose to form subgroups or teams that will be stable throughout the semester. This:

- promotes bonding between students, increases their sense of security and confidence.

- simplifies logistical and technical handling and tracking (unless you opt for randomly created teams and use a platform that allows you to do this in one click).

If you opt for stable teams during the semester, you may want to consider:

- designating roles in the team (in rotation):

- moderator

- secretary

- chief happines officer (someone who ensures that all team members feel comfortable and at ease, for example, by monitoring their non-verbal language)

- etc.

- formalize the students’ evaluation of the quality of their team meetings.

For example, you can ask them to set aside the last 5 minutes of the meeting to orally highlight what they appreciated about the contribution of others or to proceed with a formative evaluation of each person’s contribution (peer evaluation).

You may prefer to change the composition of subgroups or teams. This:

- promotes more dynamism, cognitively destabilizes students and allows students to have new (short) encounters (and network).

- is simple if you systematically use the 1-click random team creation feature, if your videoconferencing platform offers it.

- reduces the impact of dropouts and absences (particularly significant in small teams).

Tips for preparation and facilitation

To ensure the smooth running of student meetings in which you will not be participating (or not at all times), make sure that students have the technical privileges to:

- enter their videoconference room

- activate their camera and microphone

- share their screen

Make it clear to students how to instantly reach you during their team or subgroup meetings (email, MIO, chat in Teams, etc.).

To encourage student participation, invite students, either in teams or in subgroups, to take turns systematically at the beginning of the meeting (each team member should speak in turn). This will create a sense of community, break the ice by creating a culture of speaking up, but will also ensure that everyone has mastered the tools. (Don’t wait until the end of the semester to realize that a student hasn’t learned how to solve their microphone problem and that’s why they never spoke).

When a large group meeting follows a subgroup or team meeting, make it clear to the students what time they will be joining the plenary, so that they can manage their time accordingly. Broadcast a reminder countdown (5 minutes, 1 minute, 30 seconds…) before bringing students back to the main room or asking them to come back.

Encouraging participation and establishing good habits

At the beginning of the first or second session:

- Gently insist that those students who can, activate their camera.

(Note that bandwidth may be an issue for some students. Other students may be in environments that do not allow them to switch on their cameras or on devices that do not have cameras. Check your institution’s policy on activating webcams and recording sessions). - In large group sessions, make each person responsible for:

- activating their own microphone when speaking

- deactivating their microphone

- Asking to speak through the status indicator, by virtually raising their hand or through chat

- Let your students know what you want them to do with the chat. Do you want them to ask their questions? Can you keep track of what’s going on in the chat room while you teach? Do you encourage your students to interact with each other in the chat or do you want to keep it focused on questions that are directed to you?

If students develop these good habits in large groups, they will be more functional in your absence in subgroups and teams.

Sharpen teamwork skills

Students do not always know how to work well in a team, and sometimes the difficulties of teamwork seem to be exacerbated at a distance. To help them:

- Formalize the necessary preparation work before the teamwork or discussion time.

- Model and address expected attitudes and behaviours by circulating through the teams (e.g. the notion of constructive criticism).

Editor’s Note

If you are particularly interested in getting students to do teamwork at a distance, also read Profweb’s featured report on this topic.

Active pedagogy and the pedagogical relationship are also possible at a distance.

Let’s get out of the straitjacket that molds a synchronous distance course into a webinar where learners are passive and the only engagement possible is cognitive.

Get inspired by what you can do in the physical classroom to energize your distance courses and optimize your students’ learning. For example, the Vignettes de pédagogie active de Polytechnique Montréal, mentioned earlier, were designed primarily for face-to-face teaching, but many of them lend themselves very well to distance learning. And don’t forget to cultivate the pedagogical relationship that you naturally have with your students, even at a distance!

It’s up to you to dare!

References

- Beattie, G. and Ellis, A. (2017). Channels of human communication. In The psychology of language and communication (chapter 2), Routledge.

- Kozanitis, A. (2015). La relation pédagogique au collégial : Une alliée vitale pour la création d’un climat de classe propice à la motivation et à l’apprentissage. Pédagogie collégiale. 28(4) Association québécoise de pédagogie collégiale. https://aqpc.qc.ca/sites/default/files/revue/kozanitis-vol_28-4.pdf [in French]

- Lison, C. (2017, Feb. 1). Classe inversée: de l’enseignement à l’envers pour un apprentissage à l’endroit.

. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bNg86sZHNRI [in French]

- Michaelson, L. K. and Sweet, M. (2011). Team-Based Learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 128(1). Wiley.

- Prégent, R., Bernard, H. and Kozanitis, A. (2009). Enseigner à l’Université dans une approche-programme: guide à l’intention des nouveaux professeurs et chargés de cours [in French]. Presses internationales Polytechnique.