Digital Tools to Leverage the Power of Peer Assessment

Teachers spend countless hours correcting student work because feedback is critical to students’ learning process. Regrettably, an important portion of such feedback is not understood or deemed irrelevant by students, or worse yet, left unread. How can we get students to understand the important learning that happens when they interact with feedback given during assessment activities? One answer is to have them engage in the process themselves, in the form of peer assessment.

SALTISE (Supporting Active Learning & Technological Innovation in Studies of Education) hosted a webinar on peer assessment on January 29, 2021. Five teaching professionals shared how they integrate it in their classes, and which digital tools they use to streamline the process.

Editor’s Note:

Some of the platforms presented require a subscription or institutional license. However, similar projects can be conducted using other, free tools or platforms.

Recording of SALTISE’s webinar Empowering Student Learning: Ways to Leverage the Power of Peer Assessment

Peer assessment: what, why and how

Straightforwardly put, peer assessment is an activity in which students evaluate work submitted by their peers with the aim of providing meaningful feedback. This provides students with direct experience with:

- understanding the learning standards (through the use of a rubric);

- the criteria used to measure the level and quality of the work being evaluated, related to these standards.

Peer asssessment differs from typical forms of peer grading in that it focuses more on feedback and improvement and less on merely assigning grades. It is also a reciprocal process in that students both give and receive feedback. It offers advantages to teachers and students alike.

Benefits for teachers:

- Timely and plentiful feedback

- Improves students engagement and collaboration, production value and product quality

- Makes critical and higher-order thinking observable

Benefits for students:

- Better understanding of the subject matter

- Improved self-regulation

- Deeper understanding of learning standards

- Heightened awareness of discipline-related culture and discourse

While many discussions on peer-assessment have focused on the quality of the assessment received, Chris Shunn from the University of Pittsburgh brought up strong research support for the notion that most of the learning happens on the giving side. That’s right; the benefit to learners mostly comes in providing feedback to others. Research shows clear benefits of peer assessment exercises in that it prompts students to reflect and engage with the assessment criteria and standards on a deep level.

In addition, while giving peer feedback, students also develop the metacognitive and self-regulatory skills and knowledge required to understand and to act on feedback they receive, from the teacher and peers. This also explains why in-depth self-assessment is more effective than peer assessment limited to “short generic positives” like “great work!”.

Schunn pointed out that, for that reason, teacher intervention should be minimal, and limited to a sampling of the peer feedback being shared. In fact, a comment made repeatedly or collectively by fellow students is just as valid, and likely more convincing, than a one-off teacher comment. This frees up teacher time to strategically address pain points observed in a review of the peer feedback given:

- Common errors

- Issues that students were unsure or unable to address in each other’s work

Providing grades for the helpfulness of comments tends to have a powerful effect on raising the quality of the comments and also empowers students. As described by several guests, some of the most important dimensions of peer assessment come from interactions between learners as human beings. Peer assessment:

- can help a class build a sense of community on the trust that peers may provide answers;

- normalizes the process of learning from mistakes;

- goes beyond field-specific knowledge, as providing constructive feedback is a transferable skill.

Among the best practices for peer assessment, teachers’ demonstration that they value the practice goes a long way.

Peer assessment practices and tools

Jaclyn Stewart (University of British Columbia) — ComPAIR

Jaclyn Stewart from the University of British Columbia (UBC) set up a “choice project” in her Organic Chemistry class. Her students worked with ComPAIR, an open-source tool developed by UBC that is free to use. The project encouraged students to connect course content to their life, and allowed them to choose their presentation format.

Quickly, Stewart realized it was not sustainable to grade 150 such elaborate projects. It also didn’t make sense to her that she was the only person to see these projects. She decided to integrate peer assessment through ComPAIR, based on adaptive comparative judgment.

Students are presented with 2 documents and they’re asked to decide which one is better on a certain criterion or on a set of criteria. It’s easier for students to use that innate ability to compare than to use a detailed rubric that they would need a lot of training to apply with precision. This makes it an accessible form of peer assessment:

- The teacher creates the assignment and instructions.

- Students can submit their work directly in a text box or upload any kind of media file.

- During the period of comparison, students are given several sets of other students’ work and asked to compare them on the criteria provided.

- Finally, students are given the opportunity to review and reflect on their work.

Michael Dugdale (John Abbott College) — Peerceptiv

In his Physics class at John Abbott College, Michael Dugdale noticed that in lab reports, students often measure the validity of their outcomes by weighing them against the textbook answer, which dilutes the kind of questioning and critical thinking that underpins science. To counteract this and infuse his class with scientific culture, he used Peerceptiv to simulate the peer review process that happens in the publication process of scientific articles:

- Students write their lab report based on a set of specific instructions. They have a strict deadline to submit the first draft of their report.

- Then, they enter the assessment phase, in which each student is asked to assess between 3 and 5 copies of fellow students based on a teacher-provided rubric. This also exposes the students to the meaning of the rubric used for summative evaluation at the end of the process.

- Once they receive their peers’ comments, students can “back-evaluate”–assess the validity and quality of the comments they received–and edit their copy before submitting their final draft for evaluation by the teacher.

Alice Cherestes and Chloe Garzon (McGill University) — Visual Classrooms

In Organic Chemistry, Alice Cherestes from McGill University, started out by giving 2-stage exams on the Visual Classrooms platform. She noticed her students showed a clear desire for quick expert answers, and decided to use the platform for formative peer assessment activities to track her students’ thinking and understand where they struggle.

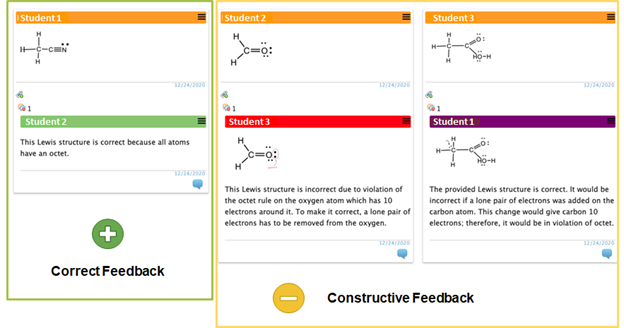

She and her teaching assistant Chloe Garzon used the platform to post formative assignments that correspond to the content learned in class. After the student completes the assignment and submits their answer, a switch is flipped in the program and the student can then:

- view all the responses their classmates have posted

- analyze these responses

- provide feedback in one of two ways

- by providing positive feedback to a correct answer

- by providing constructive feedback to an incorrect answer

Visual Classrooms makes it easy for students to give feedback correcting an answer or reinforcing a right answer

This way, they hoped to shift the point of view from simply memorizing facts and content to a more holistic understanding of the material. Giving feedback to peers helped the students train their brain to spot patterns that didn’t only serve them well in organic chemistry, but in their other classes as well. At the end of the semester, 82% of the students affirmed that both receiving and giving feedback had helped them to learn.

Anna-Liisa Aunio (Dawson College) — Span Nureva

Anna-Liisa Aunio teaches Sociology at Dawson College. She uses group projects based on scaffolding feedback and assessment. More specifically, her students work on case studies of Montreal neighbourhoods used as a canvas to test ideas, and use peer assessment and presentation skills. The software she uses is called Span Nureva, but a similar process can be set up with collaborative documents in Microsoft 365 or Google Drive. Aunio’s goal is for students to recognize feedback and to institute accountability within the group:

- Students are divided into groups at the beginning of the semester and are assigned particular neighbourhoods. They collect data and information about them to forward the goals of their group and respond to the actual assignment.

- They can see other groups’ work at the same time, so they have a testing space for their ideas. Groups provide feedback to other groups on sticky notes.

- Finally, the students respond to the feedback, so they discuss the feedback received within their group, whether or not it’s valuable to them, and then they respond to it by revising the work.

Using the principle of digital sticky notes, students comment on each other’s work, and are then asked to discuss and act upon the feedback received.

The following tables, recap how each of these teachers uses peer assessment in their classes, based on information provided by SALTISE.

| Process | Flexible, rubric provided by teacher (as simple as “which is better” or more detailed) |

| Unit of work being assessed | Assignment (written work, file uploads – including media files) |

| Frequency | I used 1 x per course, many use it more frequently |

| Assessment purpose | Summative for a “Choice Project”. Often used formatively |

| Level of reciprocity | Flexible. I had students assess three pairs of others’ work. 1-to-1 or 1-to-group |

| Purpose | Peer learning, encourage students to think about their “audience”, reduce instructor grading load |

| Context/ tool/ environment promotes | Value of multiple sources of feedback; practice applying criteria to a piece of work→ leading to better understanding of standards |

| Process | Highly structured (rubric provided by teacher) |

| Unit of work being assessed | Lab report (large) |

| Frequency | ~ 3 times / semester |

| Assessment purpose | Formative |

| Level of reciprocity | Individual accountability N×(1–1) (assess others) + ~N×1 (receive feedback from others) |

| Purpose | Promote epistemic growth in science. |

| Context/ tool/ environment promotes | Trust in the practices/ standards of the community (b/c of the anonymity of comments) |

| Process | Loosely structured & scaffolded (rubric emerges from students) |

| Unit of work being assessed | Problem sets (small) |

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Assessment purpose | Formative |

| Level of reciprocity | High collective accountability Individual to individual & Many to individual |

| Purpose | Increase peer to peer learning (increase & improve peer feedback) |

| Context/ tool/ environment promotes | Trust in the peers (group) & the value of peers’ feedback/ knowledge (increase epistemic belief) |

| Process | Loosely structured |

| Unit of work being assessed | Semester long project (large) |

| Frequency | 3 times/ project |

| Assessment purpose | Formative |

| Level of reciprocity | Group-to-group and back again Negotiation Accountability |

| Purpose | Peer learning Revision before final submission |

| Context/ tool/ environment promotes | Multiple sources of feedback that are sometimes conflicting Trust peers in course and group Constructive feedback from peers and responses from students |

Conclusion

In the last part of the webinar, the panelists discussed 4 challenges that commonly arise when implementing peer assessment:

- Students trusting each other and the process

- More time and cognitive demand on students

- Initial effort from teachers

- Logistics

Using digital platforms to organize peer assessment help alleviate some of the logistical pain points and can reduce time investment for teachers and students alike. Continuous use of peer assessment over the course of the semester helps normalize a student-centered learning process and dispels the notion that failure is final. It also shows that mistakes are essential to learning and that learning from our mistakes and those of others ultimately determines our success as students move through a holistic process from learning to mastery.

Editor’s Note

Further information and resources are available on the SALTISE website.