How to Integrate Creativity into an Instructional Design Strategy?

Creativity is an essential 21st century skill. Instructional designers and educators at all levels of education are increasingly questioning themselves on how to incorporate creativity into learning activities.

On October 31, 2017, the Canadian Association of Instructional Designers (CAID) presented its 6th series of webinar workshops entitled “Instructional Design and Creativity”. Two invited speakers contributed their point of view on this theme:

- Margarida Romero, Director of the LINE (Laboratoire d’Innovation et Numérique pour l’Éducation) at the University of Nice Sophia Antipolis and Professor of Educational Technology at Université Laval

- Richard A. Schwier, Emeritus Professor of Educational Technology and Design at the University of Saskatchewan

Workshop 1 – Digital Collaborative Creativity in Education

Margarida Romero presented the first workshop titled “Designing, Supporting and Evaluating Co-creative Problem Solving Activities with Digital Technology.”

Margarida is interested in designing learning activities that develop creativity. Echoing Ken Robinson’s TED Talk Do schools kill creativity? (2006), she questions herself on the importance of integrating creativity into education, given that automation is becoming an increasing part of professional tasks. In this context, creativity becomes a societal issue. How can teachers develop creativity in a classroom-based or distance educational context?

In the LINE framework, this issue is addressed through a complementary approach combining educational research and teacher training. This concrete collaborative and interdisciplinary research project is carried out with actors in the field.

In the CoCreaTIC project, the team explores how to develop co-creativity, defined as collaborative problem-solving leading to a solution that is considered “original, relevant and useful by a reference group.” (Romero and Barberà, 2015)

A Few Myths about Creativity

Many teachers associate creativity with the arts or certain subject matters only. They wonder if it is possible to integrate creativity in a field like science. This is one of the most widespread myths surrounding creativity. The #5c21 tool provides a reference framework for developing “techno-creative” projects involving 5 distinct 21st century skills, regardless of the subject matter:

- Critical thinking

- Creativity

- Collaboration

- Problem solving

- Informatics thinking

The 5 key 21st century skills identified in the #CoCreaTIC project.

In psychology, creativity is sometimes perceived as an individual trait that can be measured. For Margarida Romero and her colleagues, creativity is not a quantifiable skill. They believe that creativity is a contextual process. Thus, they rely on the evaluation of the creative process rather than the appreciation of the resulting artefact.

Given that creativity is not an individual trait, the team identifies 3 learning situations in which creativity can be expressed:

- On an individual level, through a learner’s attitude conducive to creativity (creattitude), in the search for solutions.

- In a team (co-creativity), where creativity can be influenced by factors such as diversity or learning climate.

- On the part of the teacher who, based on the context or certain constraints, can be pro-creative in his way of designing learning activities.

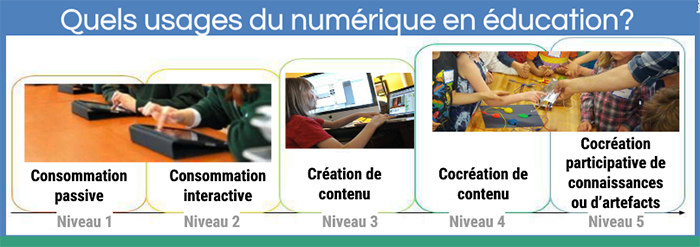

In some cases, digital tools can support creativity. Conversely, they can also hinder it when used in a rigid manner. Consequently, teachers should aim for the two highest levels on the continuum:

The different ways of using technology in education can be categorized into 5 levels based on their intricacy. Image from Margarida Romero’s presentation slides, a CAID webinar presented on October 31, 2017.

How to Implement a Techno-Creative Activity in the Classroom?

Setting up a techno-creative activity may take a certain amount of time, especially to establish a climate of trust and mutual support among students. Those who perform well in a formal setting may be reluctant in a co-creative context. Margarida recommends approaching this attitude in a direct way, by explaining the importance of digital creativity. This discussion could lead students to realize that creativity is part of all fields and could encourage them to embrace it. Adequate support has to be planned and this time should be seen as an investment, since co-creation is a cross-curricular skill, transferable to other contexts.

For a techno-creative activity to be successful, it has to meet certain criteria:

- Take place in a collaborative context

- Offer a creative margin, both in the process and the solution. This does not entail giving complete freedom to the learners. The teacher provides appropriate guidelines depending on the activity.

- Have practical use beyond the learning situation (interpellation of professionals, the wider community or social networks).

- Present a challenge or a complex problem. Students should be able to push further than they would individually.

Workshop 2 – Collaboration and Creative Design of Educational Tools

The second workshop, presented by Richard A. Schwier, was titled “On Becoming Creative in Instructional Design.”

To open the discussion on the importance of creativity in education, Richard departed from 3 propositions:

- Creativity is not a “characteristic” or “talent” people have or don’t have.

- We are all creative, even though formal schooling tends to curb creativity.

- Environments either nurture or discourage the exercise of creativity.

What are the environments that foster creativity in non-traditional design areas (such as the humanities, social science or education)? Often, these students learn in contexts different from those found in the fields of architectural or technological design. To offer its students a similar experience, the Educational Technology and Design program has turned to a studio approach that mimics the design studio environment.

Creative Collaboration in a Studio Approach

The studio approach is characterized by:

- Shared learning spaces accessible at all times

- Embedded learning and sharing of knowledge

- Formal and informal critique

- Collaborative and individual work

- Iterative development

- Public products of learning

- Community ethos

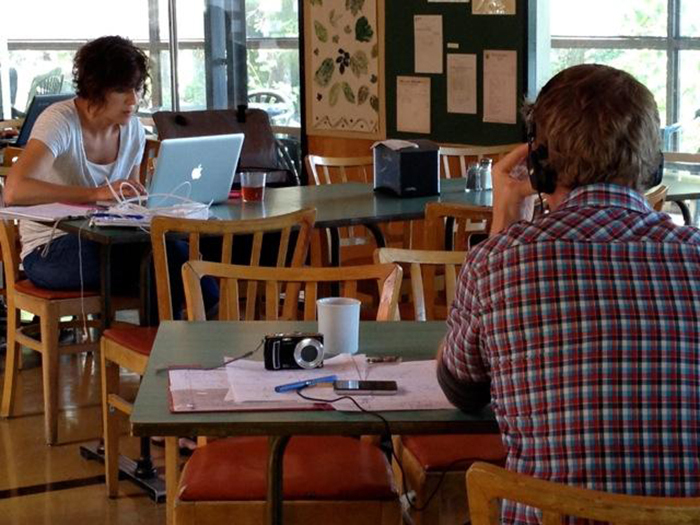

The studio approach offers an environment allowing learners to work individually as well as collaboratively. Photos from Richard Schwier’s presentation slides, a CAID webinar presented on October 31, 2017.

2 Examples of the Studio Approach

In order to illustrate the studio approach, Richard presented 2 examples of his own courses in instructional design.

In his course on video design, students participated in a camp experience set in an environment that could be considered hostile to technology.

- This facilitated the development of a community of learners as students had to work together to solve problems.

- The instructor worked with the the students, generating a constant feedback loop.

- Participants did not merely work to be evaluated; rather, learning occurred iteratively.

- This also introduced an element of serendipity, which Richar considers crucial to creative thinking.

In another course, Advanced Instructional Design, students collaborated in hybrid teams to fulfill pro-bono contracts for real clients.

- Team meeting and client meetings taught students a great deal about actual client problems and encouraged them to find solution sets.

- During the development phase, students’ work was critiqued informally.

- Students were confronted with problem-solving challenges that were less predictable and even messy – just as in real life.

- The studio experience culminated in a final product presentation, which allowed for formal assessment of the competency and its associated skills.

Final product pitch in front of clients. Photos from Richard Schwier’s presentation slides, a CAID webinar presented on October 31, 2017.

Benefits and Challenges

The studio approach offers a number of distinct benefits over more traditional instructional methods:

- Learners are exposed to “precedent” – they have the opportunity to analyze solutions other than their own and exchange feedback on various authentic situations.

- Scaffolding is individual instead of teacher-generated. This ensures all learners progress in a balanced manner that is tailored to their needs and context.

- Exceptional learning happens because students get to know the problem, the clients and each other very well. This leads them to realize that, as instructional designer, engaging deeply in the project paves the way for innovative solutions.

As any instructional method, the studio approach comes with its lot of challenges:

- Having easy and continuous access to a collaborative space may be difficult in an institutional setting. Online platforms address the problem of access, but may be less conducive to authentic collaboration.

- A lot of energy is required from everyone involved. Teachers need to carefully consider project planning and management, while students need to fully invest themselves in team collaboration.

- A lack of standardization may leave certain students insecure, while requiring a lot of flexibility and adaptation from the instructor.

Upcoming Workshops

CAID offers other online activities on different aspects of instructional design, including creativity. We invite you to consult the workshops calendar for more information on upcoming workshops, and to sign up for them.