During the webinar, Magalie Fournier-Plouffe presented some of the activities she created in 2021, in ascending order of complexity.

Revision Bingo

Magalie Fournier-Plouffe started creating bingo cards for her students long before 2021. She uses the My Free Bingo Cards site, but there are several others with similar features. The site allows you to generate bingo cards from a list you provide. This can be a list of:

- words

- symbols

- numbers

- mathematical equations

Card formats can be customized. They can be 5×5 cards, like traditional bingo cards, or another format. The visuals of the cards can also be customized.

A bingo card created by Magalie Fournier-Plouffe for her students in her Western History course.

The game is simple: students are asked questions whose answers appear on the cards. They must place a token on the square corresponding to the correct answer, if it’s on their card.

If more words are supplied to the application than there are squares on each card, the application distributes the words randomly across the cards. Magalie supplies exactly the same number of words as there are squares, so that all students have the same words on their cards, but in different places.

A sense of competition pervades the classroom, but the students know that the game involves a significant element of chance.

Magalie Fournier-Plouffe proposes a series of challenges to the students: after one person has managed to complete a line (bingo!), the next challenge is to make an X or get all 4 corners and, finally, get a full card. If all the students have the same elements on their card, but in different places, everyone is supposed to get the full card at the same time. When some people can’t (because they didn’t know the answer to a question), Magalie asks them which boxes they’re having trouble with. Together, the students in the group try to remember and explain the associated question.

The activity lasts 15 to 20 minutes with a 5 × 5 card. It could be shorter or longer, depending on the number of questions you want to ask.

Since the questions require short answers, they focus on declarative knowledge.

Crosswords

There are several applications for creating crossword puzzles. Magalie Fournier-Plouffe named Armored Penguin, and I’ve already written an article on Eductive [in French] about the Crossword tool from the Centre collégial de développement de matériel didactique (CCDMD), and the Crossword content that can be created with H5P.

These applications generate a crossword puzzle from a series of words and definitions.

The grid can be completed by students individually or in teams. (Magalie encourages them to do so as a team).

Like many other activities presented during the webinar, crosswords can be used for review, but also for diagnostic assessment. For example, Magalie Fournier-Plouffe created a crossword puzzle on the history of Quebec. She submitted it to students at the start of the session to evaluate their knowledge on the subject, given that many had not attended high school in Quebec. She then had them complete it again at the end of the session, so that they could see their progress.

According to Magalie, the activity took 10 to 15 minutes to complete. (The time obviously varies according to the size of the grid and the complexity of the questions).

Like bingo, this activity is designed to test the acquisition of declarative knowledge.

Post-it game (Guess Who?)

Here, students are divided into teams of 4 or 5. Each student sticks a card featuring a historical figure on their forehead (without looking at it first). To guess their character’s identity, students take turns to ask the other members of their team “yes” or “no” questions. Magalie Fournier-Plouffe suggests that her students ask questions related to the course, for example:

- Is my character from [such and such a country]?

- Is my character associated with [such and such a historical period]?

- Is my character associated with [this historical event]?

- etc.

Students have the right to consult their course notes.

Magalie used Canva to create pretty cards to present each character, but a simple sticky note with the character’s name written on it would work just as well.

The fronts of 3 of the cards created by Magalie Fournier-Plouffe

On the back of each card, Magalie writes important facts about the character. Once a student has identified their character, they must share these facts with their team.

Magalie Fournier-Plouffe also suggests adapting the Guess Who game. You can replace the characters with people related to your discipline (and invite your students to ask questions related to the concepts covered in the course, rather than about the characters’ appearance).

In both cases, you need to have studied several different characters in the course for the game to be interesting. Magalie Fournier-Plouffe suggests adapting the game by replacing the characters with concepts.

Magalie sets aside 15 or 20 minutes for the post-it game. She has a few extra cards to hand out to teams that finish faster, so that everyone stays busy.

Timeline

For this activity, inspired by the Timeline game, Magalie Fournier-Plouffe uses the same Canva template as for the Post-it cards. On the front, she includes historical events (related to Quebec history, in this case). On the back, she provides a brief description of the event and its date.

Front and back of a timeline card

Students play in teams of 4 or 5. Magalie Fournier-Plouffe provides each team with a “centre” card, to be placed on the table at the start. Then, each person receives 4 cards, in a stack, and must initially look only at the front of the card on top of their stack. The 1st person playing must place their 1st card on either side of the central card, depending on whether the event occurred before or after the one already on the table. By turning the card over, the team can see the date (and read the text) and check whether it has been placed in the right spot. If this is not the case, the card is put aside in a common pack and the person who played it must draw a new card to put in their pile. If, on the other hand, the card has been placed correctly, the person who played it has only 3 cards left in their pile, and the turn goes to the next player.

The aim for each player is to place all of their cards.

Magalie Fournier-Plouffe also organizes an inter-team competition: each team wants to be the 1st to have placed all its cards.

The activity lasts 20 to 25 minutes. Of course, this may vary depending on the number of cards in play. Magalie points out that this was one of her students’ favourite games in Fall 2021.

Magalie Fournier-Plouffe mentions that this activity can be adapted to any course where an evolution or timeline is involved. In fact, the game is very similar to an ice-breaker activity used by teacher Pierre Mondor in a cinema course [in French]. Magalie Fournier-Plouffe also suggests that the activity be adapted to courses where students have to memorize a procedure in several steps.

Jeopardy!

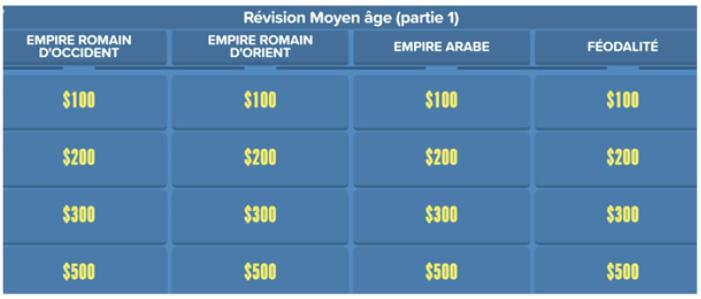

For a more substantial revision activity before an exam, Magalie Fournier-Plouffe uses the Factile application. Factile reproduces the Jeopardy! game. Factile has already been featured on Eductive.

To simplify the game, Magalie dropped the idea that answers must be questions (and vice versa). Questions are organized by theme and hidden behind amounts of money. Students, in teams of 3 to 5, try to win as much (fictitious) money as possible by correctly answering the hidden questions. Lower amounts hide simpler questions, while higher-paying questions require more explanation.

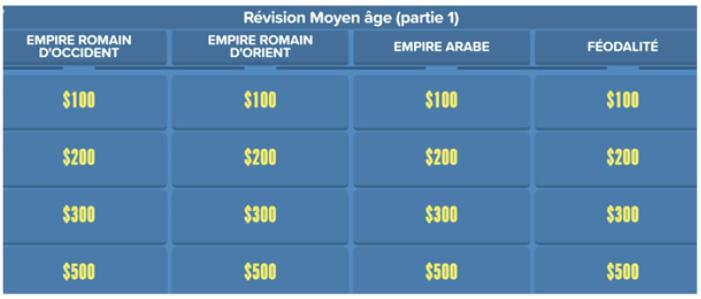

Screenshot of a game board created on Factile by Magalie Fournier-Plouffe. As this was a game created to review for a midterm exam, 4 categories with 4 questions each was sufficient. For a final review, 5 categories (or more!) of 5 questions each can be created.

Magalie Fournier-Plouffe creates the teams herself. She tries to balance them so that each team has a real chance of winning. This prevents teams from starting the 45-minute game knowing they won’t win. She explains to the students that the fact that she creates the teams allows them to work with people other than their friends.

At the end of the game, when all the questions on the board have been covered, the special final question appears (which Magalie doesn’t tell her students in advance). Teams can wager an amount of money (the entire amount they’ve accumulated previously or a portion of it). If a team has the right answer, it wins the amount wagered. Otherwise, they lose it. This sometimes leads to unexpected twists and turns and helps to even out the odds.

What’s more, after it has been played in class, the game can be shared with students for further revision.

During the webinar, Magalie Fournier-Plouffe provided a link to play with the questions she used in her Quebec History course [in French].

Since the answers are given verbally by the students, more complex questions can be asked than in a Kahoot! game, for example. Moreover, members of the same team can supplement each other’s answers, which encourages collaboration.

Magalie Fournier-Plouffe said that Factile was a huge success with her students, and she was surprised that the site wasn’t better known. However, she was less enthusiastic about the character limit for questions and answers.

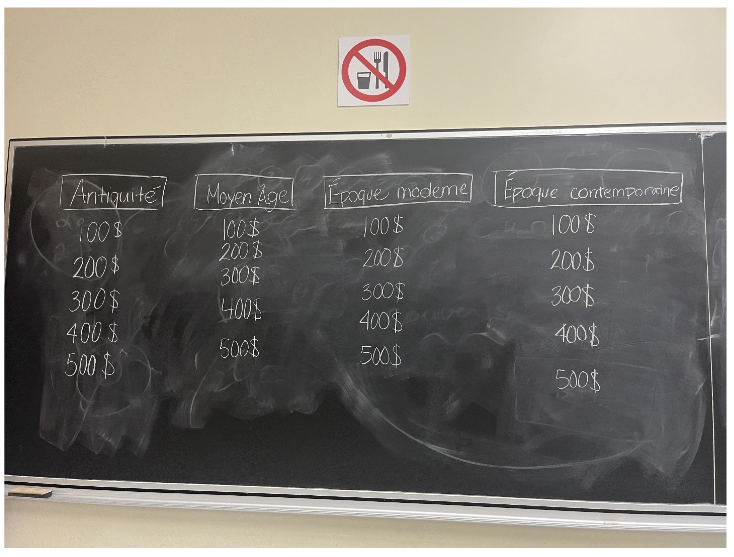

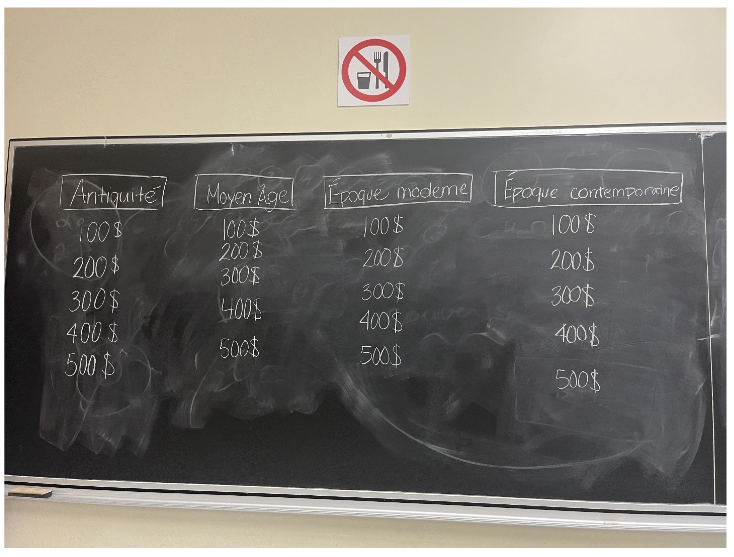

With the paid version of the game, the cell phone of one student on each team can be transformed into a buzzer, making the activity even more fun, and making it easier to manage speaking turns. This is not possible with the free version. With the free version, a team must raise their hand to answer. It’s then up to the teacher to check off the team’s answer on the screen to validate it. Magalie also shared how, during a wifi outage, she facilitated the game without Factile, recreating the board by hand.

A “technology-free” version of the game, during a wifi outage.

The length of the game varies according to the number of questions, but Magalie Fournier-Plouffe usually allows 30 to 45 minutes.

Escape game

Working in teams, students have to find the answers to riddles (which are exercises).

For the Winter 2023 session, Magalie Fournier-Plouffe offered her students a role-play based on the Prohibition era. To enter a speakeasy, students had to find a secret code made up of answers to 5 riddles. Each riddle was contained in an envelope. Students had to submit their answer to the 1st riddle for Magalie to validate it in order to gain access to the 2nd riddle, and so on.

In one envelope, for example, students found a series of maps of Quebec in different eras (Lower Canada, United Canada, etc.). Each map was marked with a number (23, 14, 6, etc.). The students had to understand that their task was to place the cards in chronological order to obtain a sequence of numbers to present to the teacher.

In another envelope, students found a charade (which Magalie Fournier-Plouffe had ChatGPT compose in French [and which was subsequently adapted by Eductive to work in English]):

- My first is a synonym of “deception” and an antonym of “pro.”

- My second is giving food in the past.

- My third can be making a mistake or violating a rule.

- My fourth is a quantity (of food) allocated to a person or an animal for one day.

My whole involves 4 “elements” that you have to name to get your next envelope.

Thus, students had to name the 4 provinces that made up Canada at the time of Confederation to obtain the envelope.

Game duration varies according to the complexity and number of puzzles. In the case of the game based on the Prohibition era, the game lasted around 20 minutes.

The game can be built from a set of revision exercises you already have, but structuring them in the form of an escape game makes the revision activity more engaging for students.

Student perceptions

Magalie Fournier-Plouffe surveyed her students at the end of the Fall 2021 session. The results were very positive.

- For the statement “Overall, these revision activities have helped to increase my motivation and attention in class”:

- 73% of the 25 respondents answered “strongly agree.”

- 27% answered “agree.”

- No one answered “somewhat agree” or “disagree.”

- For the statement “Overall, these activities were effective in reviewing the course material”:

- 81% of the 25 respondents answered “strongly agree.”

- 19% answered “agree.”

- No one answered “somewhat agree” or “disagree.”

I really liked that you took the time to review the material from previous classes, as we could pinpoint the things that needed revision on our part. Plus, it motivates us before starting the class on a Friday night, so thank you 😄

—Comment from a student in the survey [translated from French]

What’s more, Magalie Fournier-Plouffe found that her group’s average was higher than usual, and absenteeism was lower.

All this inspires playing a little in class!