To encourage my English as a Second Language (ESL) students at Cégep Limoilou to believe that they can learn, I designed metacognitive activities to show them how to learn. Here I present these activities, which have yielded positive results, so that you can adapt them to your own courses.

Have you ever heard…

“English is not my strength” or, on the contrary, “English comes to me intuitively”: these are two comments I often hear when students explain their lack of motivation in a general education ESL course. In both cases, these students have a preconceived idea of their ability to learn English that negatively affects their motivation.

No matter what subject you teach, chances are you have heard some variation of this in your classes. Indeed, this attitude is not limited to English or language learning; many skills across all disciplines (e.g., math, manual aptitude, or sports) are considered “talents.”

Mindset: believing you can learn

To better understand why both positive and negative perceptions can lead to a lack of motivation, I turned to the concept of mindset in the work of psychologist Carol Dweck.

Carol Dweck suggests that individuals have beliefs that frame how they perceive and explain their social world. These “mindsets” can lead them to view their personal qualities as static (fixed mindset) or malleable (growth mindset), which motivates them to think and act differently. This concept thus provides an interesting lens for understanding academic motivation.

People who exhibit a fixed mindset tend to:

- attribute failure to a lack of intelligence or talent

- doubt their ability to improve

- avoid threatening situations to protect their self-esteem

- feel more helpless and anxious

People who adopt a growth mindset tend to:

- attribute failure to their own effort

- work harder because they believe that they can improve if they put in the effort

- see challenges as learning opportunities

- remain more optimistic and persevering

The growth mindset is driven by a motivation to learn rather than a motivation to perform, as is the case with the fixed mindset.

That said, mindset can vary in the same person over time and situations, and it can be developed.

By promoting the activation of metacognition—the explicit awareness that a person has of their learning—I wanted to lead my students to cultivate a growth mindset in order to increase their level of motivation.

Metacognitive wrappers: learning how to learn

Metacognitive wrappers are activities, often in the form of a questionnaire, that surround a pedagogical task to encourage the learner to:

- question and reflect on their study and work habits before (and during) the task

- analyze the process and results of the task after it has been completed

Metacognitive wrappers are thus intended to enable students to improve their learning strategies and, consequently, their metacognitive skills.

Example of a metacognitive wrapper, completed in the 1st class, after writing a short text. The questions invite students to look critically at their strengths, areas for improvement, and ways to achieve it.

In my course, I integrated metacognitive wrappers into the weekly learning sequence by presenting them in my lecture notes shared in electronic format through OneNote’s Class Notebook. However, they lend themselves to many other formats:

- electronic form (Microsoft Forms, for example)

- interactive quiz (Wooclap or Genially, for example)

- oral reflection (Flip or individual interview, for example)

- paper

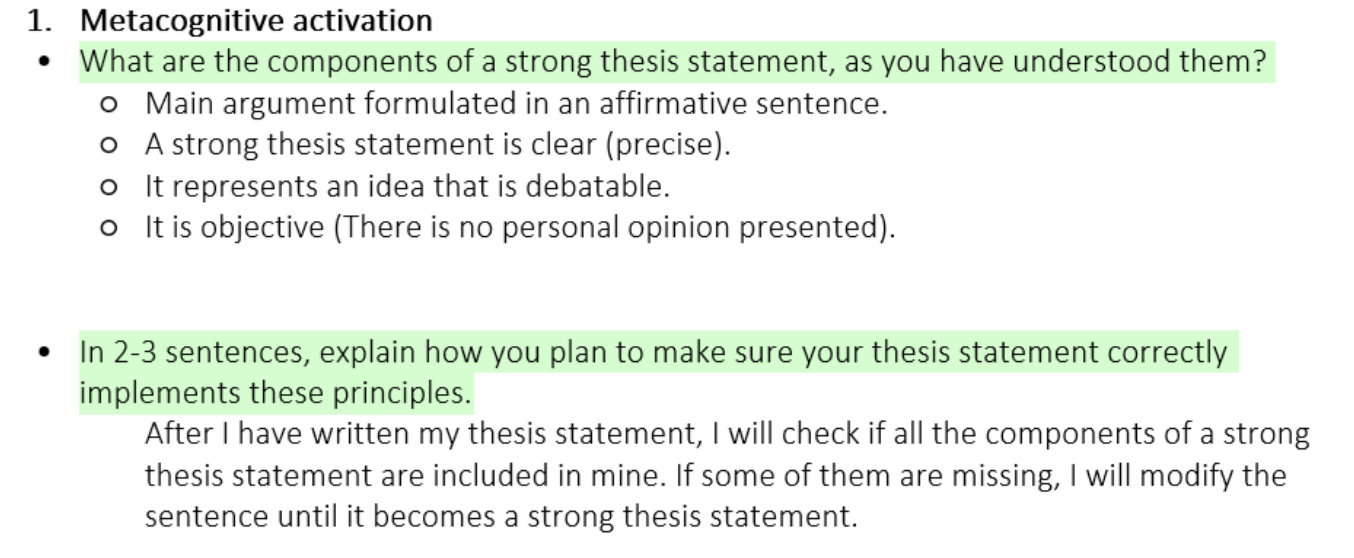

Metacognitive wrappers concern 3 important elements of learning. This is illustrated with examples concerning the thesis statement of an English essay, excerpted from a student’s notes:

- preparation for the task (knowledge and strategies)

Example of 2 questions inviting students to verbalize their knowledge about the thesis statement, and how to apply it

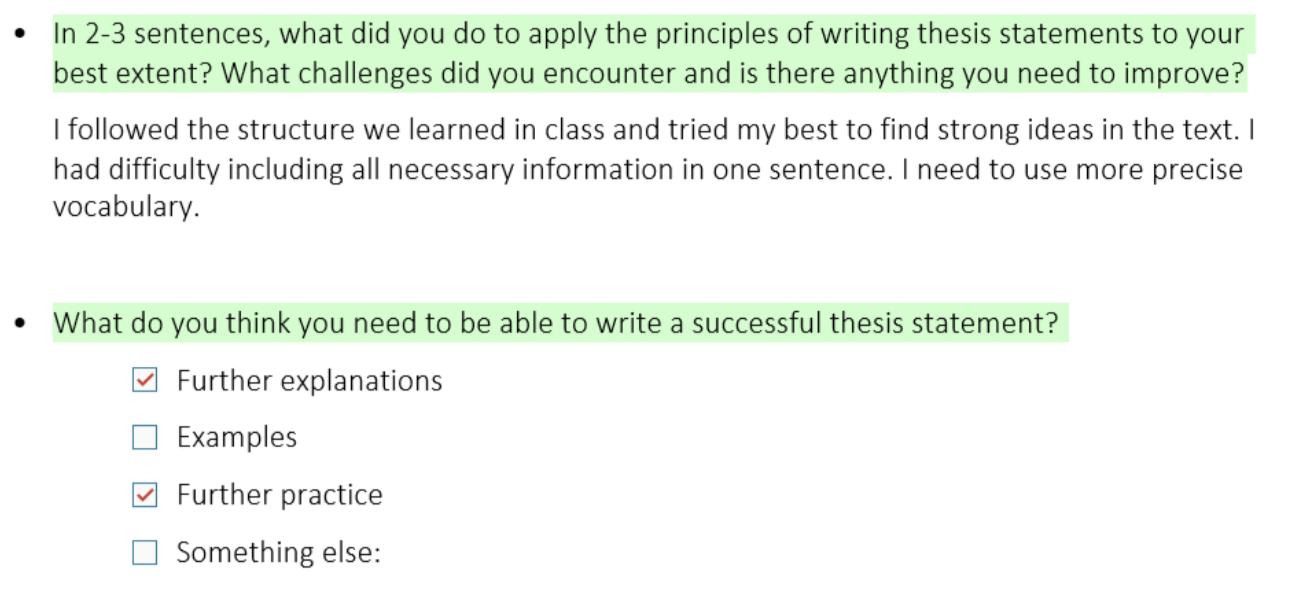

- challenges encountered and types of mistakes made

Example of 2 questions inviting students to verbalize their challenges, mistakes and needs

- potential adjustments

Sample of 3 questions inviting students to reflect on strategies used and adjustments needed or desired

By applying this principle, metacognitive wrappers are easily adapted to all contents and disciplines.

Because essays in my course always take the same form, I designed a more elaborate series of metacognitive wrappers built around the midterm assessment, in which the students were led to:

- critically question the preparation required

- use checklists to ensure objectives and requirements are met

- identify problems and establish strategies to avoid them in the future

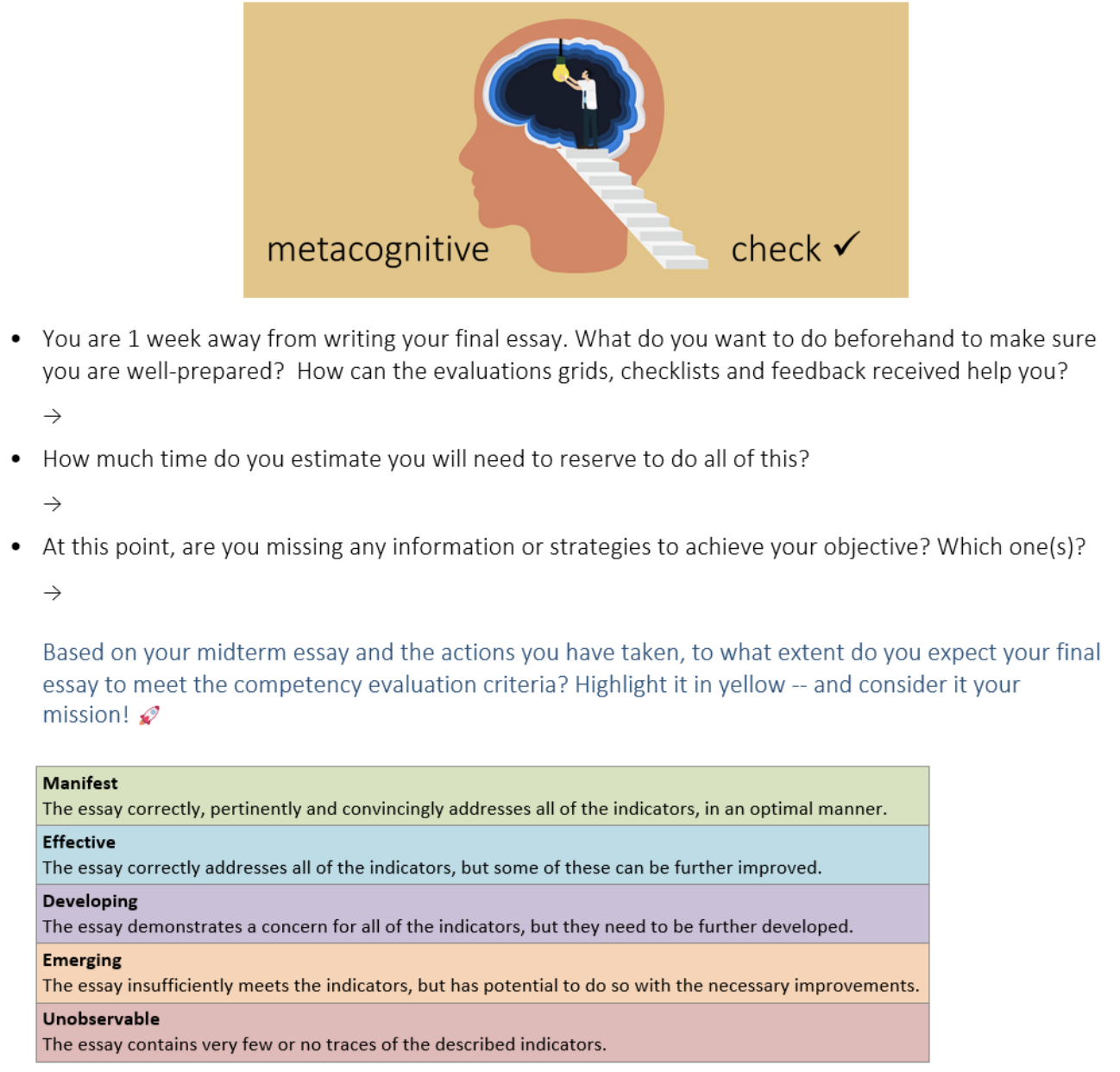

- refer to the descriptive evaluation grids to make increasingly accurate judgments about their own learning

Series of metacognitive wrappers related to the midterm essay

It is possible to adjust the frequency of metacognitive wrappers according to the needs of the course and to link them to learning, formative, or summative evaluation activities.

Their goal remains the same: to make students more autonomous in selecting and applying their learning strategies. Thus, in my course, the final metacognitive wrapper invites them to set a goal for the final evaluation and to establish the means and strategies to achieve it.

A study demonstrating the influence of metacognitive wrappers on mindset

To understand the potential influence of these metacognitive activities on students’ mindset, I conducted, as part of my Master’s degree in College Teaching with Performa, an exploratory study during the fall 2022 session. About 50 people enrolled in 2 of my groups in the course 604-103-MQ English Culture and Literature at Cégep Limoilou agreed to participate.

The study had 2 components:

- quantitative: a Likert scale questionnaire on mindset, motivation and metacognition, administered in weeks 1, 6, 10, and 15

- qualitative: semi-structured interviews with 6 volunteers, conducted after the final grades were posted

Preliminary results based on quantitative data processing show that over the course of the session, there was a statistically significant positive increase in scores indicating metacognitive ability and growth mindset. There is also a significant correlation in the data between metacognition and mindset.

These observations may therefore suggest that the gain in metacognitive skills helped to develop growth mindset. In other words, learning how to learn would enable students to increase their belief that they can learn.

Although further analyses of the data are needed and it would be interesting to repeat this study in other courses, these observations indicate the potential and value of the intervention.

Over to you to wrap things up!

In addition to positively influencing students’ metacognitive skills and growth mindset, metacognitive wrappers also had other positive impacts:

- Their implementation encouraged me to consciously plan the learning that took place.

- Students were led to better identify the essential learnings and their purpose.

The relevance of metacognitive wrappers is not limited to English or ESL courses, as they can:

- take different forms

- be adapted to all courses and disciplines

- be integrated into different learning and evaluation activities

- be used regularly or more sporadically

Versatile and easy to insert into a teaching sequence, metacognitive wrappers have a definite potential, and it would be interesting to observe their outcomes in other college disciplines. Are you planning to use metacognitive wrappers in your courses? Share your ideas and tips in the comments!

Great article Andy! Learning how to learn seems to be a key to student success and your wrappers are a great tool to help students on their way. I will be sure to pass this article on to our ped counsellors and academic advisors.

Angie

Thanks, Angie!